Written by: Gabrielle Rozumek

Edited by: Jennifer Baker, Will Dana, and Claire Shudde

Illustrated by: Paola Medina-Cabrera

Imagine that, over the years, your vision has become blurry and it’s not what it used to be. You wake up a few days after your 70th birthday, and though you’re usually greeted by the bright morning sun, today it’s not so bright – there is a dark spot in your vision. You blink a couple times to try and get rid of the spot and quickly realize it’s not going anywhere. Shortly after, your doctor diagnoses you with age-related macular degeneration (AMD). There are temporary treatment options but no cure. Ultimately, your vision loss is permanent and that dark spot in your vision will likely grow larger until you can’t see at all.

This imaginary scenario is statistically likely to become part of your lived experience. As we get older, our chances of suffering from vision loss and blindness increase drastically. And even though approximately 1 in 28 Americans over 40 suffer from blindness or low vision, there are no treatments or cures for vision loss. Once you lose your vision, it’s gone.

Because of this, the goal of many researchers in vision science is to develop new therapies to make vision loss not quite so permanent, either by reversing or preventing vision loss in the first place. This is the case for Dr. Kapil Bharti, a Senior Research Investigator at the National Eye Institute, who has turned to an unconventional source for inspiration: blood.

Blood-to-stem cell transplants: a new type of treatment for vision loss

In Dr. Bharti’s lab, scientists and clinicians are working together in an attempt to rescue the vision of twelve patients with advanced stages of retinal disease. In this once-in-a-lifetime clinical trial, the selected patients have their blood drawn and converted into stem cells–cells with the ability to become any cell type in the body. When these stem cells are fed with certain nutrients, given specific signals, and put in the right environment, they are redirected to become specialized eye cells. After about two and a half months in the laboratory, those cells are ready to be transplanted back into the eye with the hope of rescuing the patient’s vision.

If Dr. Bharti’s trial works, these findings would transform the outlook for someone with AMD or other advanced vision loss. Instead of waiting to slowly go blind, someone with this type of vision loss would be able to walk into a clinic, have some blood drawn, and return a few months later to have those same cells (now converted into specialized eye cells) transplanted back into their eyes to prevent further vision loss!

This study was all made possible by the Bharti lab’s ability to grow retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) in a dish. RPE is key to maintaining good vision because it forms a layer of support under the light-sensitive layer at the back in your eye called the retina. You may have heard of the photoreceptors in the retina, which detect light and send electrical signals to the brain, enabling us to see the world around us (Figure 1). Though RPE doesn’t detect light, it plays an underrated but critical role for vision: garbage collecting.

Figure 1. Anatomy of a healthy human eye and retina. Light enters through the front of the eye and lands on the retina in the back of the eye. The cells that collect light information are known as photoreceptors. The cells that support the health of the photoreceptors are known as retinal pigment epithelial cells.

Every time light enters your eye and hits your retina, energy from the light makes photoreceptors shed chunks of their cells off as debris (Figure 2). Without the RPE, this debris builds up over time and damages the retina. It’s kind of like a game of Tetris. As the “Tetris blocks” of debris fall, it’s the RPE’s job to keep the debris at the lowest level possible. If the debris build up too high, you lose, and photoreceptors die off!

Figure 2. When RPE disappear due to disease, photoreceptors start to die off. This is partially because the RPE are responsible for clearing debris and harmful molecules. Without the RPE the debris builds up, causing the photoreceptors to be unhappy and leads to a disease state.

Winning this “Tetris game” is crucial for maintaining retinal health. Over time, photoreceptors and RPE are not able to repair as well due to disease or aging. If photoreceptors die off, we start to lose vision, and if the RPE dies off, the photoreceptors supported by the RPE will die. Once we lose photoreceptors, whether due to direct damage or indirect loss because of RPE death, we cannot make new ones, and there is no current treatment to restore the lost vision.

However, if we were able to successfully transplant new RPE into the eye, these cells would become garbage collectors for the remaining photoreceptors. Here’s an analogy: if your street’s garbage collector stopped coming, there would be a buildup of trash in the street. This might block normal day-to-day functions like driving through the intersection or package deliveries. The consequence of this might be that residents leave, and the area is left barren. If the neighborhood suddenly got a new garbage collector, the trash would get picked up and the normal activities could resume. Plus, with someone coming frequently to clear trash, that might encourage the remaining residents to stay! This is similar to what happens during an RPE transplant: if RPE no long is able to clear debris, photoreceptors will die, resulting in vision loss. Transplanting lab-grown RPE salvages the remaining photoreceptors because debris clearance is restored. By rescuing the remaining photoreceptors via RPE transplant, we may be able to salvage the patient’s remaining vision as well.

While we will have to wait some time before the blood-to-stem cell treatment could become a routine part of vision care, this technology can also be used to study fundamental biology questions in the eye. If we can grow and maintain these specialized eye cells like RPE in the lab instead of implanting them back into patients, we can study how a healthy eye develops and what happens when an eye falls victim to disease.

Lab-grown mini eyeballs: an efficient, animal-free method for fundamental research

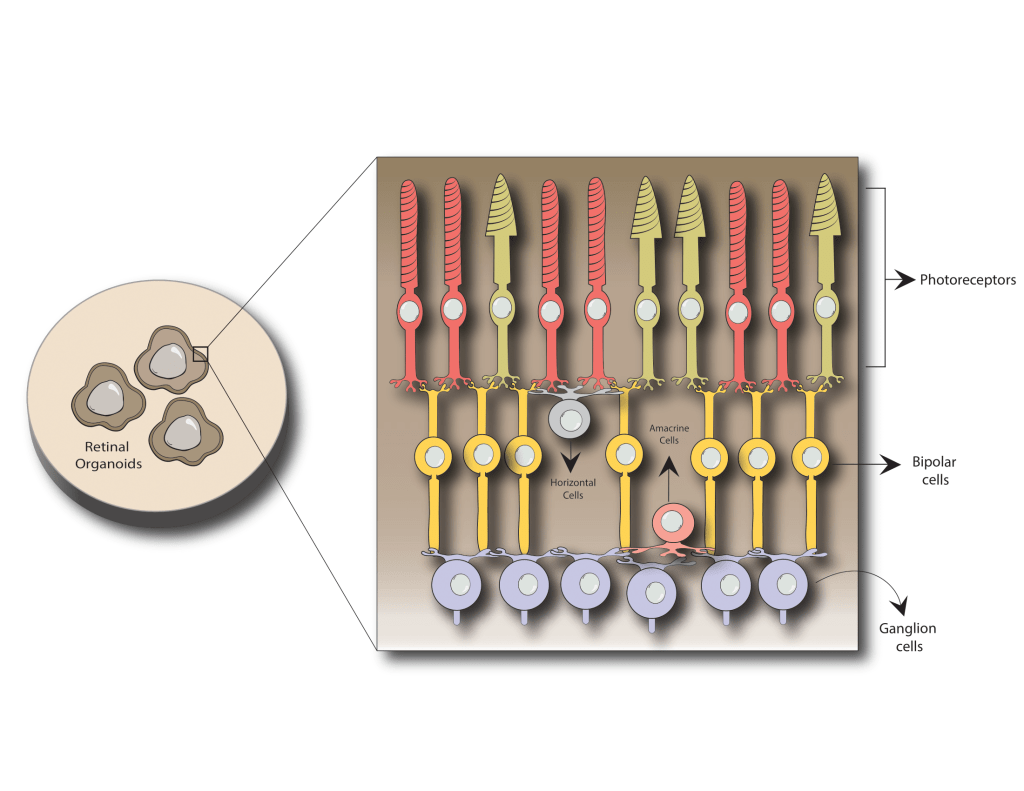

One way these specialized eye cells can be used is to create lab-grown mini eyeballs, or as they are referred to in the field, retinal organoids (Figure 3). Organoids are 3D balls of cells that, with the right environment, food, and chemical signals, can become almost any tissue or organ in the body–in this case, the eye. If managed correctly, these balls of cells are made of many different cell types, which are arranged in layers in the same way found in human eyes. In fact, retinal organoids contain all the cell types found in the human retina and are organized like a mature human eye. Even crazier, these balls of cells act like an eye and can respond to light!

Figure 3. Retinal organoids are 3D balls of cells about the size of the point of a sew needle. Inside retinal organoids, many of the cell types we see in a healthy human retina can be produced. While RPE cells can be made in retinal organoids, they often die off early on and that’s why they are not shown here. Having all the cell types in retinal organoids allows us to study them without having to harvest eyes from mice. Even crazier– these organoids can be grown in culture for over 200 days!

You might be thinking to yourself, “This is too much…lab-grown mini eyeballs with the ability to respond to light…count me out!” Fear factor aside, retinal organoids have massive potential to help us understand the development and disease progression of an organ. By using retinal organoids made from human cells, we can understand eye disease and development better than when using lab animals. For example, a key feature of a human eye is an area of the retina known as the macula, which is essential for central vision. Mice, on the other hand, do not have a macula. This makes it difficult to study disease related to macular degeneration in mice, one of the most commonly used lab animals.

Retinal organoids are also extremely efficient since you can make many organoids at one time. From one plate of cells, you can generate almost 200 retinal organoids, each one being approximately the thickness of a sewing needle! This means researchers can scale up experiments and complete studies faster than would be possible when studying people or mice, while using fewer resources. Recently, there has been a huge push across the world to reduce the number of animals used in research by replacing them with other models when possible. Organoids are one viable solution to reach this goal: they are currently being used to test drugs and genetic interventions before trying them in people and could be used for other purposes in the future. By replacing mice with retinal organoids when possible, the time needed for the development of drugs and other treatments for eye conditions will hopefully be reduced, getting quality treatments to patients in less time.

The future of vision science will include these new techniques in the clinic and the lab

To change the course of treatment for vision loss, both fundamental research and clinical trials are going to be necessary. There is outstanding collaborative work being done by clinicians and scientists to potentially restore vision in patients in ongoing clinical trials, like the trial from the Bharti lab! However, it took about 15 years of research and many safety checks along the way to get the current blood-to-stem cell clinical trial up and running. It’s also important to recognize the shortcomings of a complicated procedure like this one. The current procedure involves scientists growing the cells, clinical trial managers, and retinal surgeons doing the surgeries and checkups, all resulting in a cost of millions of dollars per patient! We will need the next generation of vision scientists to think creatively about how we could standardize and simplify this procedure to be able to bring this therapy out to the millions of patients who need it. We have learned so much from lab-grown cells in the past decade and there is still so much to uncover. Through fundamental and clinical research, this technology can help patients to see the future and scientists to shape the future of vision science, one lab-grown mini eyeball at a time.

Gabbi Rozumek is a Ph.D. candidate in the Molecular & Cellular Pathology program studying the genetics of inherited eyes disease such as extreme hyperopia (very small eyes). She graduated with a B.S. in Biology from Roger Williams University in 2020. Gabbi is a first generation college student, a retired collegiate athlete, and a dog lover. In her spare time, she indulges in making baked goods, running or playing soccer, and hanging out with her two senior dogs (Petey & Lola). She is also passionate about science outreach and strives to make STEM education accessible to students from disadvantaged backgrounds. This includes bringing science lessons to local Detroit middle/high schools or flying students to the University of Michigan for an all expenses paid week-long short course in developmental biology through Developing Future Biologists.