Written and illustrated by: Jacquelyn Roberts

Edited by: Jennifer Baker and Christina Del Greco

“Structure implies function” is a phrase often repeated by biochemists to describe how molecular machines work in the body. For a protein, structure is formed as its string of amino acids twists and folds into a globular final form. If amino acids are beads on a string, then the folded protein is the final necklace or finished work. This “final form” lends clues to the protein’s role in the cell. Often, like a lock and key, proteins and their chemical partners ft together perfectly. But for a long time, we had absolutely no idea how or why proteins reproducibly twist and fold in the same way every time to adopt a consistent final form.

Christian Anfinsen first postulated that the amino acid sequence determines the final form of a protein in 1973 and received a Nobel Prize for his work (1). However, the daunting task of predicting the structure of a protein from only the order of its amino acids remained a challenge for nearly 50 years. At the time, the rules governing protein folding weren’t understood completely, and the computational power required to make such predictions seemed out of reach. So, scientists took to experimentally determining the structure of their protein of interest. To do this, they painstakingly crystallize their protein of interest and bombard it with x-rays, or irradiate a flash-frozen sample with electrons. A successful experiment generates 2D images that are used to create a 3D model, into which the amino acid chain can be fit by hand. These de novo, or “from scratch,” renderings of proteins take months to complete and are dependent on the quality of the data collected.

In 2021, artificial intelligence (AI) brought us AlphaFold (2), a program developed by Google’s DeepMind that takes the amino acid sequence of a protein and predicts what its 3D structure might look like. AlphaFold does this by using all of the previous structures that scientists have experimentally derived and uploaded to the global Protein Data Bank (PDB). In the two years since its release, AlphaFold has predicted the structures of over 200 million proteins (3), changing the way biologists and chemists plan studies and analyze results. Armed with DNA sequences which can be translated into amino acid sequences, any scientist can predict what their protein of interest might look like in seconds. Experimentally verifying this prediction can take months or even years, but now scientists have a starting point they could have only dreamed of decades ago when de novo protein design was the norm.

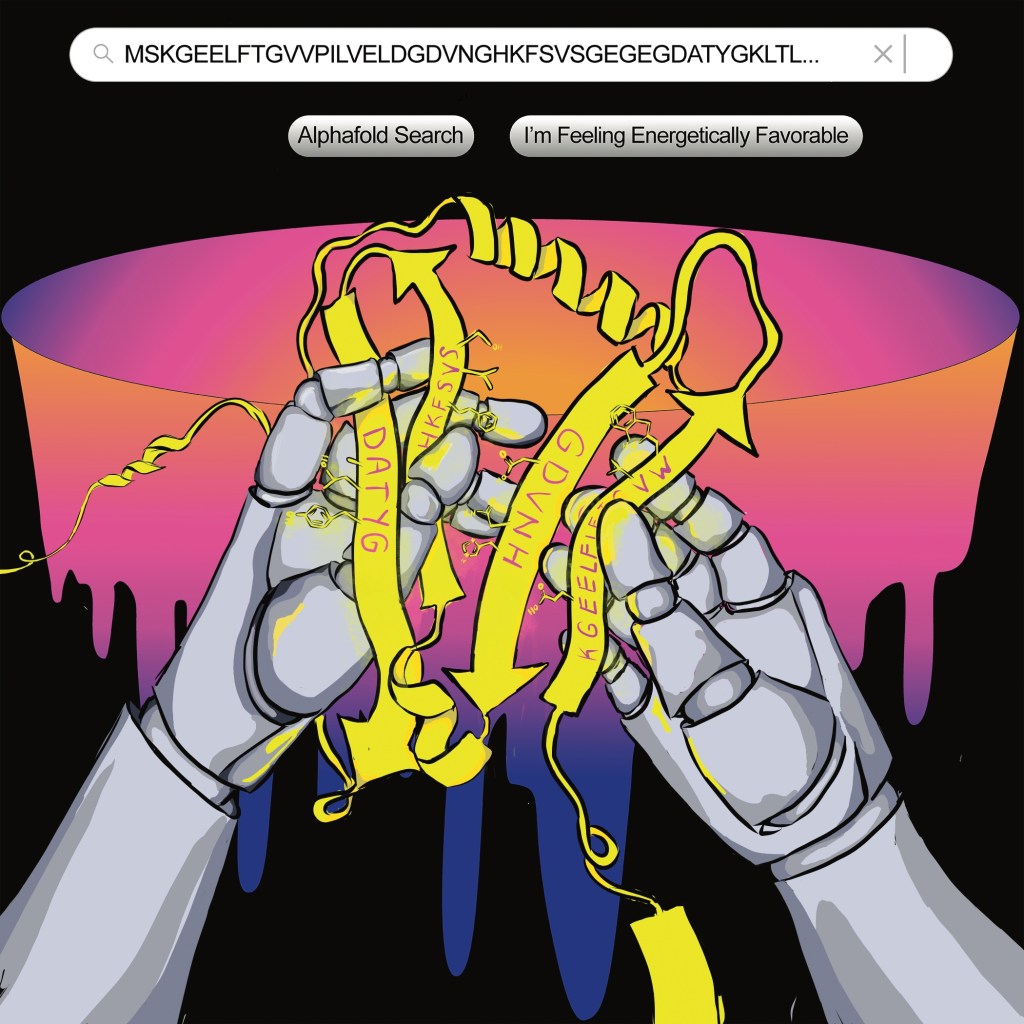

This artwork anthropomorphizes AI, lending human qualities to the incredibly computational task of predicting the shape of a protein. Human-like robot hands are entwined in the beta sheets of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) as if one could knit with a string of amino acids, connoting both the artistry and analysis involved in determining a protein’s structure de novo. The protein itself, YFP, is derived from bioluminescent jellyfish and is routinely used by scientists to track the movement of other proteins through the cell, attaching YFP to other cellular proteins like travelers attach colored tags to their luggage so it stands out among a sea of black suitcases. This technique is only useful, however, if YFP is attached to the protein at an innocuous site – if the YFP is attached to the protein being tracked at a location that interferes with its function, the experiment is rendered useless, and thus, in another sense, knowing the structure of the protein is essential to knowing its function. In the background is a graphical depiction of the energy landscape of protein folding. In its final form, the protein will be in a deep valley, signifying a stable conformation. Above the scene is a search bar containing the amino acid sequence of YFP, the only information needed for AlphaFold to predict its structure.

Jacquelyn is a biological chemistry grad student at UM, where she determines the architecture of molecular structures used by bacteria to cause disease. She has always been drawn to both science and illustration, and nearly enrolled in a medical illustration program before obtaining a degree in biochemistry.