Written and illustrated by: Dana Messinger

Edited by: Olivia Pifer Alge, Julia Donovan, and Jennifer Baker

In September 2014, Ann Arbor local Chad Carr, grandson of University of Michigan football coach Lloyd Carr, was diagnosed with an aggressive brain tumor just days before his 4th birthday. His mother rallied the community for support and the #ChadTough mantra raised national attention. Meanwhile, Chad underwent 30 rounds of radiation and a clinical trial, unfortunately passing just 15 months later at the age of 5.

Brain tumors recently overtook leukemia as the most common cause of cancer-related deaths in children. While leukemia is a more frequent diagnosis, much progress has been made in treating pediatric leukemias, whereas pediatric brain tumor treatment has seen little advancement beyond radiation therapy.

Roughly half of all deaths from brain tumors in children are due to pediatric high-grade gliomas (pHGGs), which are divided into groups based on the mutations they contain and where in the brain they appear. High-grade gliomas in the middle structures of the brain are called diffuse midline gliomas (DMGs) (Figure 1). Chad was diagnosed with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), a particularly aggressive form of DMG located in the pons, which has an average survival after diagnosis of less than 12 months, despite being most common in children aged 5 to 10 years old.

Children with pHGG often experience symptoms that are common with brain tumors, including a loss of normal motor function as well as facial weakness and vision problems. DMGs are particularly dangerous because they form in the region that controls bodily functions such as heart rate and breathing. Surgery is often too risky as it is not worth risking damage to these important brain structures. Since DMG is a particularly grim diagnosis and there are limited treatment options, it is very important to understand how this type of cancer develops to design more effective therapies.

What type of mutation drives DMG formation?

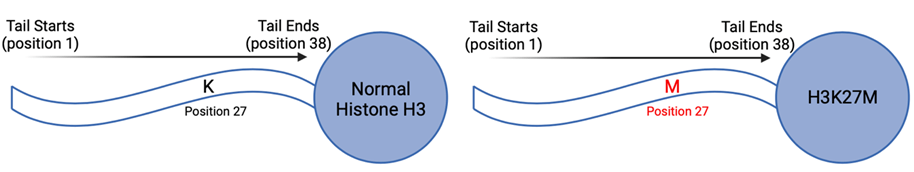

Cancers can be driven by a variety of gene mutations impacting processes such as cell division, DNA repair, and metabolism. The majority of DMGs share a common mutation known as H3K27M, which impacts epigenetics. Epigenetics modify gene expression rather than the DNA code itself, so H3K27M interferes with how and when genes are typically expressed. The H3K27M mutation occurs specifically in a protein called histone H3, which is where it gets the first part of its name from. The K27M part of its name indicates that the mutation changes the twenty-seventh amino acid, or protein building block, from lysine (K) to methionine (M) (Figure 2).

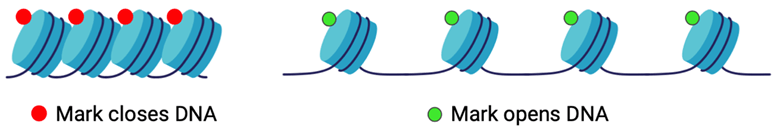

Part of the reason that the H3K27M mutation causes epigenetic changes is because of the role that histones play in how a cell’s DNA can be expressed. Histones are small, round proteins with tails that keep the DNA in every cell wrapped up and organized, making them partially responsible for which genes are expressed. They function in groups of eight, called octamers, to allow the nearly six feet of DNA present in each cell in our bodies to coil up around them. Small chemical tags, or epigenetic markers, get added to histones at specific locations on their tails and can directly impact how tightly the DNA can wrap around the histone octamers (Figure 3).

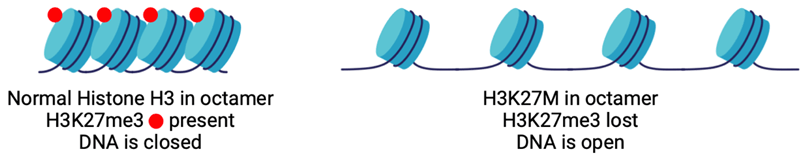

The H3K27M mutation specifically interferes with how loose or tight the DNA can wrap around histones. It prevents the proper placement of an epigenetic marker that “closes” the DNA called H3K27 tri-methylation, or H3K27me3. Normally, a special group of proteins called polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) adds this mark to histone H3. The mutated histone, however, prevents PRC2 from placing H3K27me3 marks correctly on any of the histones in the cell, leading to a near complete loss of this “closing” mark (Figure 4). This results in the DNA being more open than it should be, which means that the key to understanding how these changes lead to brain tumor formation lies in knowing which closed genes have now been opened.

How does this epigenetic change result in tumor growth?

PRC2, whose main role is to place the H3K27me3 closing mark, is most commonly associated with regulating the timing of gene expression during the development of organs, including the brain. Genes that are controlled by PRC2 are essential for ensuring the brain is growing and developing appropriately before a child is born. It is equally as important that these neurodevelopmental genes get turned off once they are no longer needed. In a cell with an H3K27M mutation, where normal PRC2 function cannot happen, these developmental genes are expressed in an already developed brain. While this will not directly cause cancer to start growing, it does “turn back the clock” in cells with the mutation.

Cell growth is more rapid during development, so the biologically “younger” H3K27M cells, which now express developmental genes, grow faster than their mature counterparts. This raises the risk that they will eventually pick up more aggressive mutations that lead to tumor formation. Brain cells that have the H3K27M mutation will also stop performing their regular jobs to focus on growing and making more of themselves. Each new cell needs a copy of the DNA from its parent cell, but the faster a cell grows, the more likely it is that there will be random errors in the new DNA. Some of these errors will be corrected, and some will cause the cell to die, but errors in certain genes will allow completely uncontrolled cell growth and division. Cancers develop from these cells, and people will eventually start experiencing symptoms, like the vision and coordination problems seen in children with DMGs.

How is current research improving treatment options for DMG?

Researchers around the world are dedicated to gaining a deeper understanding of how this disease works and better ways to treat the children who have it. In fact, recent studies on H3K27M-mutant DMG have shown promising increases in the survival of children treated with a medicine called ONC201, which is able to restore the closing H3K27me3 mark lost with the H3K27M mutation. ONC201 is currently being investigated in active clinical trials at multiple universities in the United States, including the University of Michigan.

Though the results for this new drug are promising, research on this topic is far from complete. Foundations started by families affected by DMG work to raise the funds necessary for these studies and others like it. The ChadTough Defeat DIPG Foundation, which was started by Chad Carr’s parents, raises money for research through events like charity races, golf outings, and even an annual gala. Their mission aims to ensure that one day, families will not have to endure what they did when Chad was diagnosed with DIPG.

Dana Messinger is a fourth-year PhD candidate in the Cancer Biology program studying how two common mutations interact with each other to drive pediatric brain cancer growth. She has a bachelor’s degree from the University of Vermont, where she studied Medical Laboratory Sciences. Dana has worked in both clinical and research labs since she was in high school and is passionate about making science more accessible. Outside of the lab, she loves to spend her free time traveling, hiking, and attending concerts.