Written by Charukesi Sivakumar

Edited by Sheila Peeples, Jeremy Chen, Kate Giffin, Kristen Schuh

Illustrated by Adriana Brown

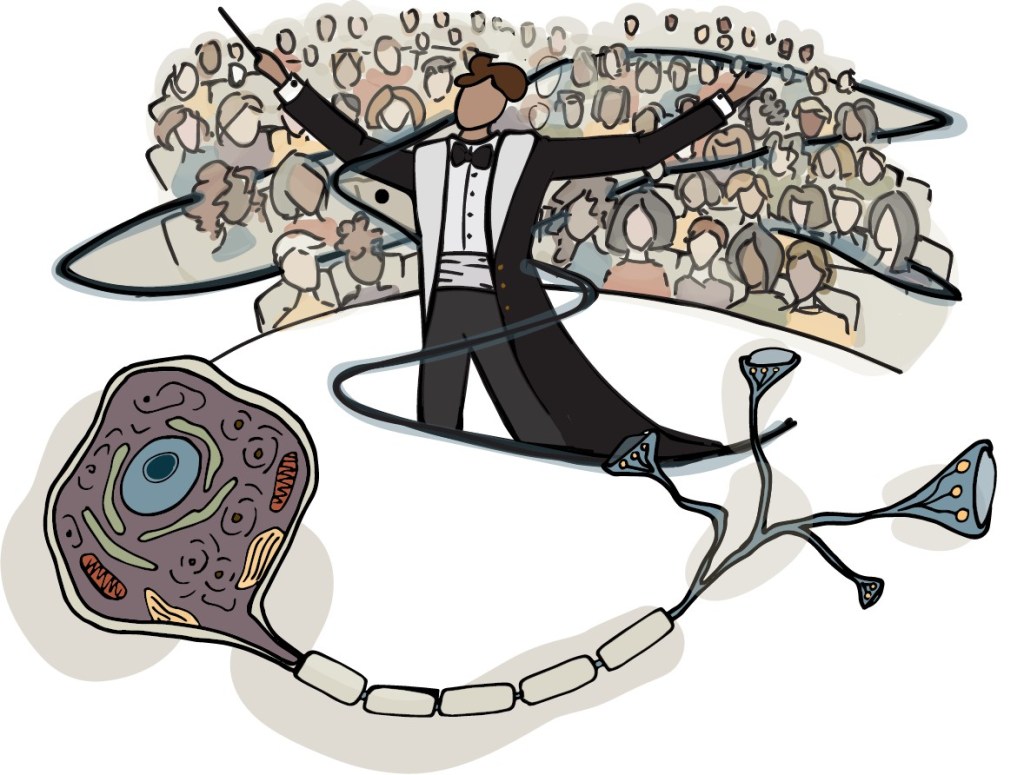

The lights dim as we, the Life Sciences Orchestra, lift our instruments. With the wave of our conductor’s baton, the music swells across Hill auditorium and enters the audience’s ears, lighting up the brain.

Movement 1: Out the Instrument and into the Brain

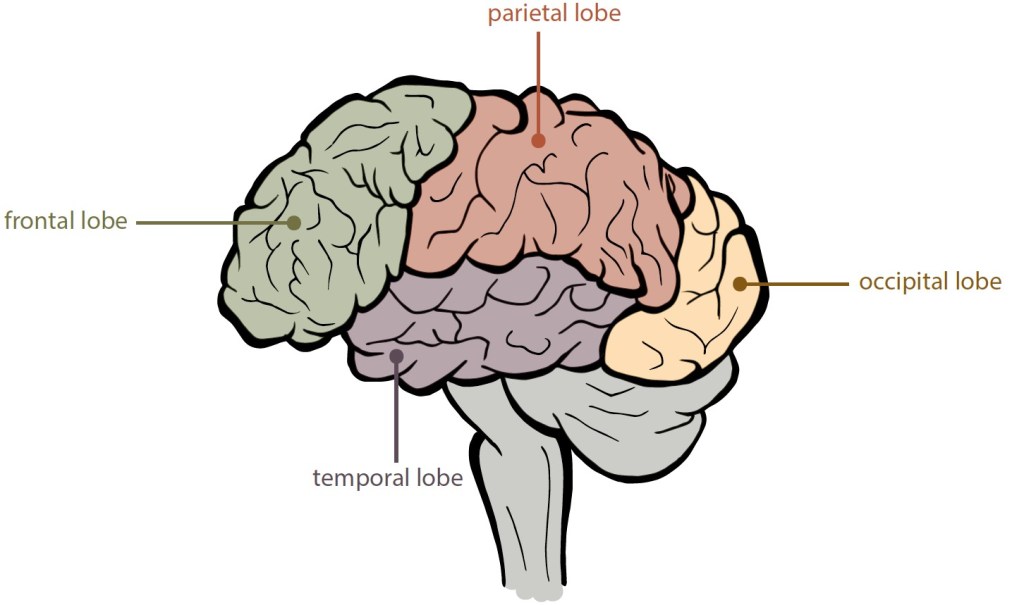

The brain is a complex machine that processes thousands of signals in every moment of our lives. But how does the brain know where to process something as specific as sounds? Our brains are split into four different regions, or lobes: frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital. Each lobe has an area of “expertise.1” The frontal lobe is the decision-making region, the occipital lobe processes visual information, the parietal lobe processes touch, and the temporal lobe is responsible for processing sounds.

Initially, sound waves pass through the ear canal into an area called the cochlea, which has thousands of little hairs called stereocilia. The stereocilia vibrate based on the frequency of sound and pass that message along through the auditory nerve which directs an electrical signal to the brain. Once in the brain, neurons, a type of brain cell, transmit that signal through synapses, or tiny gaps between neurons. Everyone sitting in the auditorium listening to the orchestra has about 100,000,000 neurons2 communicating with each other to process the music in a total of 150 milliseconds.

Interestingly, for us to process everything that music has to offer – rhythm, mood, etc. – we utilize every portion of our brain! However, there are many pieces that need to come together for the brain to process music, making it incredibly difficult for us to understand how music impacts us. Since it is so difficult, many scientists spend hours each day trying to understand what happens behind-the-scenes in our brain. Scientists3 studying music’s impact on the brain use animal models to design experiments to answer the many questions we have. In one study4, scientists showed that music prevented anxiety-like or depression-like behaviors in rodents! Rats that listened to classical music, such as Mozart, had almost no behavior changes compared to rats that underwent the same stressors without music. Why is that? The study found that listening to music reduced levels of stress hormones, inflammation, and even promoted the growth of new neurons.

Another study5 also showed that musical environments can promote the connectivity of brain regions after injury, which could be related to the increased production of neural growth factors. Neural growth factors6 promote the growth of new neurons, which is key for the development of new connections and can improve behaviors such as learning one’s environment.7 However, it is hard to say what the long-term effects of music are on neural development. Further research that needs to be done to connect the dots between the behavior changes seen in animal models to what is going on inside human brain cells.

With a final chord, we come to a silence, a quiet peace filling the room before applause begins to radiate through the auditorium.

Movement 2: A Glimpse into Music Therapy

With the benefits scientists are seeing in animal models, it is no surprise that people are using music as a way to enlighten one’s mood. When individuals are asked why they choose to listen to music,8 responses range from uplifting mood and relieving stress, to using music as a means of self-expression. There are studies9 that show that playing music or singing with other people can promote the release of oxytocin, a hormone that promotes trust and social bonding. These hormones are associated with positive and calm emotions, something that many individuals strive to achieve when listening to music.

Many scientists strive to connect their work to the medical field, and those researching the effects of music can translate their work into what is known as music therapy. Music therapy has been used in practice since 178910 and is described as the use of music to help improve one’s quality of life.11 Music therapists are licensed to use various techniques, such as directed listening, writing, or playing music, to create personalized programs addressing a patient’s goals.

Research shows that music therapy can be used for a variety of ailments, ranging from stroke and Parkinson’s disease to pain and mood disorders. Parkinson’s disease12 is a brain disorder where dopamine neurons that coordinate movement slowly die over time. Studies show that music therapy13 can help patients with Parkinson’s disease improve movement, motor control, mood, and overall quality of life.

Currently, there are no cures for mental health conditions or brain disorders like Parkinson’s disease. However, there is a positive trend14 both in the use of music therapy, as well as in research related to music therapy. To gain further insight into music therapy, more research on how music positively influences the brain is still required.

The audience leaves as we clear the stage. I’m excited to see my friends who came to watch the performance and share in the beauty of the music we all experienced.

Movement 3: Connections Through Sound

Each year, millions of people gather at venues to watch their favorite artists perform. Everyone at the show shares an immediate connection with each other through their love of the artist(s) on stage. The people on stage share a connection with each other as they are creating music with one another. In a band, an individual may start improvising and that may continue throughout the instrumentalists, each one connecting through the music to carry it forward. Within an orchestra, there can be anywhere between 20-100 people playing at once, each one needing to maintain a constant connection with those around them.

At the University of Michigan, the Life Sciences Orchestra15 was created by a group of physicians, medical students and staff who wanted to share the joy of music with others. Today, it is a 70+ person orchestra that comes together despite busy schedules to create music because it connects us all, no matter the path of life we are on. As a violinist in the orchestra, I find a sense of peace in rehearsal every week leading up to our concerts. After a successful performance at Hill Auditorium, we feel the immense satisfaction of playing challenging music and hearing the crowd cheer across the auditorium. These feelings are no mystery – the release of hormones and the thrill of a performance comes together to strengthen the connections with those around us.

A lot remains to be uncovered about how music positively affects us. However, existing studies support that there are benefits to listening to music, such as with music therapy aiding those going through life changing circumstances. Whether music is for enjoying oneself or to find a community, it is clear that the joy one gets is a shared experience. From the synapses in the brain to the biggest symphonies, we are all connected through sound.

Charukesi Sivakumar is a 3rd year PhD Candidate in Molecular and Cellular Pathology at UM, studying the development of the retina. When she’s not in the lab, you find her playing disc golf, or immersing herself in music, and finding new ways to connect with the world around us.