Written by Patricia DeLacey

Illustrated by Catherine Redmond

It was a cloudless morning in the Simien Mountains National Park in northern Ethiopia. “There,” said Esheti pointing down the cliff, spotting the geladas1 with an expert eye. Through my binoculars I saw a line of geladas amble up the sheer cliff. Once they reached the grassy plateau, I collected behavioral data. Talisman, the dominant male of a unit, was groomed by the adult female, Coco, while he puffed out his chest. His bright red chest patch and golden-brown mane looked particularly impressive juxtaposed to Tecate, the subordinate adult male in the unit. Tecate’s mane was short, his shoulders sloped inwards, his chest patch noticeably pale pink instead of red. Looking at the surrounding geladas, I noticed the variation in chest patch color across male dominance status.2 What could be the purpose of exposed red skin in a cold, high-altitude environment, and why is there variation in red color? This puzzling unique trait is putatively linked to reproductive success and sexual selection.

Natural selection, proposed by Charles Darwin, is the most well-known and most taught theory regarding evolutionary biology. By exploring and observing nature, Darwin noticed species change over time by exhibiting variations in particular traits. In response to harmful environmental stressors, those that survive get the chance to reproduce and pass on their traits to the next generation.3 However, not all variations enhance survival; he noted a trait that did not fit into his theory of natural selection: a peacock’s tail. The tail’s vivid, iridescent colors and five-foot length make it nearly impossible to hide and escape from predators, such as tigers and leopards. What pressure could have selected for such an extravagant tail? One word – females. The peacock’s tail does not aid in survival, but it instead helps the peacock “woo” choosy females in a flashy mating display.

Traits for my mate

Sexual selection focuses on traits that give an individual an edge for mating opportunities over the competition with members of their own sex. Charles Darwin first postulated the theory of sexual selection in The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex in 1871 to explain ornamentation traits, such as the peacock’s flashy tail, and weaponry traits, such as a ram’s horns. These sex-specific physical traits appear at sexual maturity and are secondary to biological sex-specific traits of genitalia. To name a few examples: lions have manes while lionesses do not; male mallard ducks sport a bright green head while females are brown; wild male gorillas weigh up to 400 pounds while females only weigh up to 200 pounds. The more intense the mating competition, the more disparate the appearance between males and females.

However, Darwin focused on male traits that females lack, such as the weaponry for male-male competition or ornamentation traits used for attracting females. As such, he had a very male-centric focus and stated that traits arise from a “struggle between the males for the possession of the female.”4 Darwin was on the right track, though it’s not as simple as competitive males and coy females. But can we blame him for his observations and conclusions?

Science prides itself in being objective. Scientific discoveries are based on evidence, systematically collected information gained through carefully conducted experiments or observations. This pursuit of objectivity has a caveat: science is conducted by humans. Each person brings a unique perspective to scientific research, but these perspectives can carry bias, unconscious or otherwise, that shape how they approach a question. An individual’s biases determine what questions are asked, how they are asked, what methods are chosen, and what methods are excluded. The larger scientific consensus can further distort this goal of objectivity.

To approach questions, scientists form testable explanations for a phenomenon, based on preliminary evidence. Evidence they choose to collect is rooted in observation. Observations are rooted in the collective consensus or perspective resulting from previous experimentation. Like all things in science, theories are challenged, tested, and revised where necessary as additional evidence comes from new investigations. Theories sometimes have room to expand as data accumulates, and the theory of sexual selection is no exception. Darwin did the best he could interpreting the data available and creating his theory of sexual selection, but the true diversity of sexually selected traits go beyond what he could have imagined.

Stay at home dads and flashy females

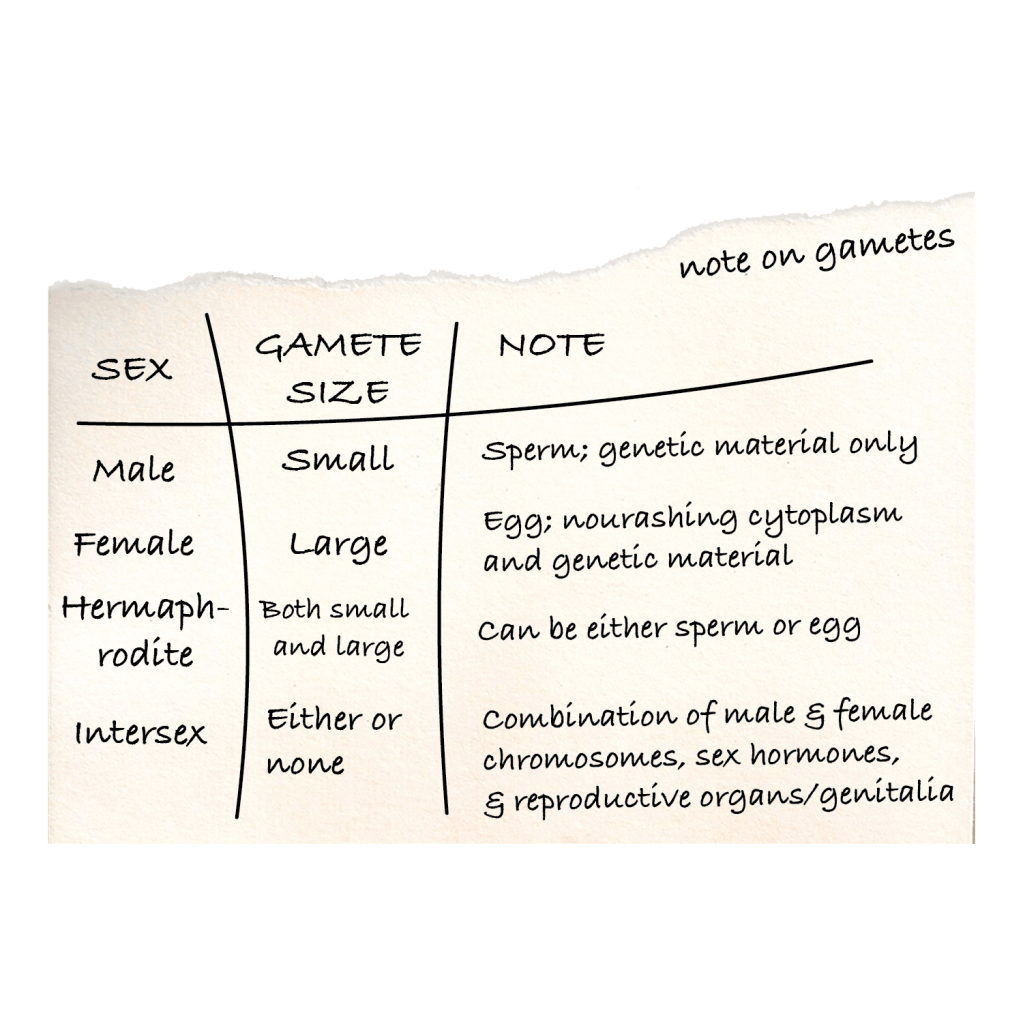

Before we delve into sexual diversity, we must ask: what defines male and female? Biological sex is defined by the size of the reproductive cell (gamete) the organism produces (Table 1).5

In sexual reproduction,6 a small and large gamete must be brought together to form a zygote which develops into an egg or fetus. The union of two dissimilar gametes, called anisogamy, is nearly universal in sexual reproduction. The sex contributing the smaller gamete (male sperm) has a smaller initial investment in reproduction than the sex contributing the larger gamete (female egg). Males can produce hundreds of thousands of sperm with little energetic investment while females are rate limited in the amount of viable eggs. Unequal investment in gamete production often corresponds to unequal investment in offspring care. Typically, this looks like males competing with each other, males mating with as many females as constraints7 allow, and females choosing high quality males to produce strong offspring.

Are males always competing for choosy females? In the Wattled jacana, a wading bird native to Panama, females are larger than males and have sharp spurs on their wings that females use to compete with one another to establish a territory and a harem of males.8 Within each female’s territory, one to three or more males defend a nest and incubate eggs laid by the singular female. In the broadnosed pipefish, a saltwater fish species in the same family as seahorses, females are again larger than males, develop brighter colors than males, and court males with a mating dance.9 One female will lay her eggs in several male’s brooding pouch where they will carry the eggs until they hatch. As such, Darwin’s theory that males always compete does not hold up with these more recent observations where females compete for mates.

What dictates which sex competes? In the case of the jacana and pipefish, females produce eggs faster than males can care for them. Thus, males are tied up with reproduction while more females are ready to mate at any given time and must compete with one another for mating opportunities. In mammals, females are responsible for offspring after birth10 because they provide milk for infants. This time commitment for them means that more males are available to mate, and males must compete with one another for mating opportunities. As such, the ratio of time it takes to reproduce between males and females in a given species largely determines who competes for mates.11

Expanding the theory

Not only are sex and reproduction important in mating, but also (non-sexual) social interactions between members of the same species. In some songbird species, when a parent returns to the nest with food, the offspring open their mouths wide and stretch up to solicit food. The color inside their mouth, called a gape, indicates immune function, where in barn swallow nestlings, red correlates to a better immune system.12 As such, parents are more likely to invest in deep red, healthy chicks because they have a stronger chance of survival. This would be an example of a non-sexual signal between parent and offspring. In 1983, evolutionary biologist Mary West-Eberhard expanded the use of weaponry and ornamentation traits in non-sexual interactions between parents and offspring or among siblings. Her theory of social selection13 suggests that interactions between individuals of the same species are chosen, both in sexual and non-sexual contexts, based on the ability to attain limited resources. Thus, sexual selection exists as a subset of social selection as a part of a species’ means of survival.

Darwin’s original theory of sexual selection has been challenged and altered over time, reflecting the impact of society’s shifting views on sex and reproduction, along with more evidence collected from species Darwin did not survey. A unique human trait, as far as we know, is to justify, validate, or approve behaviors in human society. Humans often make the misguided assumption that because something exists in nature, it is morally “good”.14 A behavior exists in wild animals because it either improves reproductive success or increases the chance of survival.

Stepping back from our perceptions and moral structures, scientific exploration should strive to identify an objective framework to discover explanations for the things we observe in the natural world. This provides a significant challenge since our experimentation is conducted under a social and cultural context, much like Darwin. Nevertheless, we should be aware of how our views impact the science conducted that our views can limit our perspective; we must remember the goal of science is to understand the natural world.

1 A monkey species endemic to the highlands of Ethiopia

2 In male geladas, dominance status is determined by mating access to reproductive females. Dominant “leader” males mate with a group of 2-12 adult females, subordinate “follower” males spend time with this group but rarely mate, “bachelor” males spend time with only other males and do not mate.

3 The theory of evolution by natural selection has continually been supported by evidence from the fossil record, biogeography, embryology, genetics, antibiotic/pesticide resistance, and even direct observation in experimental and natural settings.

5 This should not be confused with gender identity, gender expression, or sexual orientation.

6 Some species of fruit flies that have multiple sperm sizes and a few fungi have one gamete size. (Roughgarden J (2004). Evolution’s Rainbow: Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People. Berkley: University of California Press.)

7 Environmental and social

10 Some mammals like the california mouse practice biparental care where both parents raise the offspring; Gubernick D J & Teferi T (2000). Proc. Biol. Soc. 267(1439): 147-150.

11 Of course, the distribution of food, predation risk, environmental harshness, population density, and the required level of paternal care also impact these structures: it’s never a simple rule of males compete and females decide.

14 This is formally known as the naturalistic fallacy