Written by Colter Giem

Edited by Amanda Bekkala and Paris Riggle

Illustrated by Adriana Brown

Let’s take a drive.

We’ll start downtown. Somewhere in the Midwest – on the shady lawns and gridded streets of Indianapolis, or below the brick warehouses of East St. Louis. We drive in any direction; as in the rest of America, the sprawl goes wherever the cities do.1 We zip by tidy townhouses and hulking apartment complexes, which yield to cookie-cutter tract housing and gaudy McMansions, which give way to the sparse, suspicious exurbs of suburban flight. Before you know it, the road opens into the rolling fields and low hills of America’s breadbasket. Everything from the high prairies of western Nebraska to the lush foothills of the Appalachians is an almost unbroken plain of farmland.2 This is one of the most productive agricultural regions on Earth, fed by arterial rivers, hundred-mile aquifers, and the stunningly productive loess soil left behind by retreating glaciers.2 This region produces a third of the world’s soybeans and corn,* and the annual harvest can be seen from space, in great continental brushstrokes of green and brown.2,3 This expanse, along with similar stretches in Ukraine and Argentina and China, fulfills the basic goal of human civilization – providing our food.** We stop at the side of the road, by a large cornfield. It’s mid-August, and the corn isn’t ripe yet. The air is brisk and sweet, and the green stalks ripple in the light breeze.

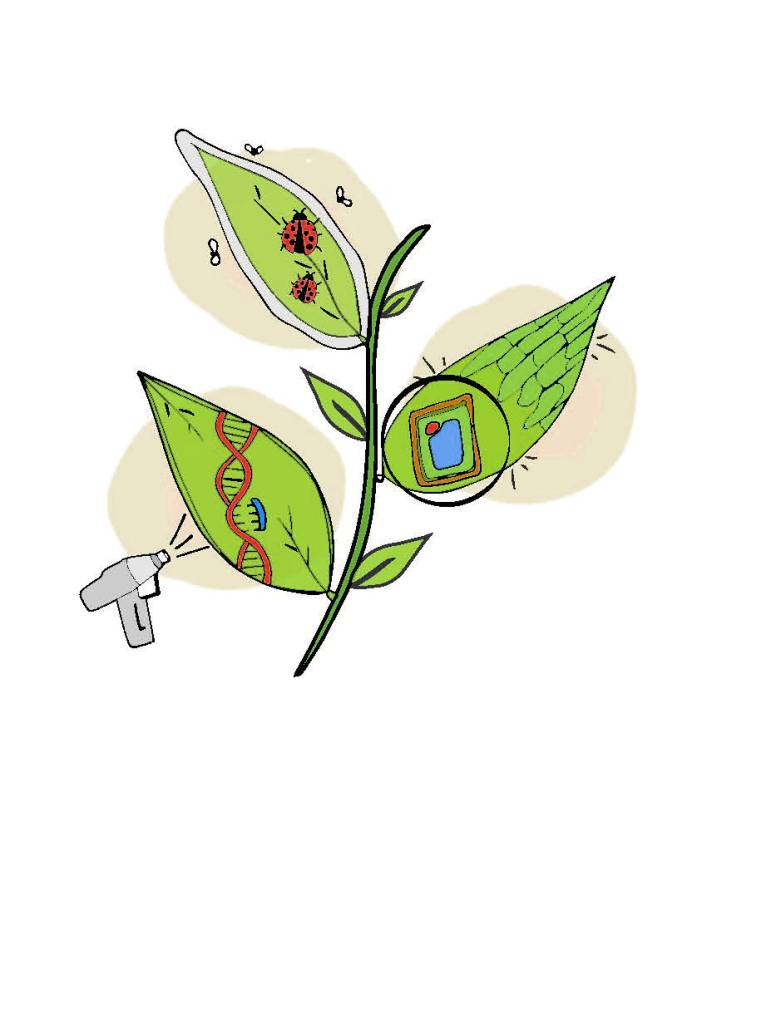

In modern parlance, this is classic flyover country. But in truth, this is a dynamic, vibrant land, where trillions of tiny battles are waged minute by minute, where the food supply of the planet hangs in the balance. Pathogens – fungi, bacteria, parasites – are as much a scourge to plant life as animal life.4,*** The U.N. estimates that 20-30% of all food produced on farms is lost to disease every year.5,† But as with all nature’s battles, this is a two-sided fight. Plants have evolved alongside pathogens for millennia, and they possess robust immune systems.6 It’s different from animals; plants don’t have our mobile, flexible, adaptive immunity, with its ability to detect and remember its vanquished foes. Instead, each plant cell operates an innate immune response.6 Generally, this is a two-branched system – receptors on the plant cell’s surface recognize bacterial molecules and activate first-line defenses, like deploying toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) to kill pathogens, or depositing new material to thicken cell walls.6,7 If that fails, they switch to the second line of defense. Specialized R proteins†† recognize the effector molecules that pathogens emit and go full scorched-earth on the cell, releasing more ROS, deploying corrosive salicylic acid, or (if all else fails) initiating cell suicide.6,8 After infections, some can even acquire a kind of epigenetic immune memory (albeit much less robust than we vertebrates enjoy) and remain in a state of hyper-vigilance for life.10 Immune responses are observed across plant species – in corn, entire groups of cells commit simultaneous suicide to deter pathogens,11 while many tree species grow hardened tissue around wounds to wall them off from surrounding healthy wood.12,††† In general, these systems work; the fact that our planet wears a global coat of greenery shows that plants thrive amid nature’s onslaught.

* And 7% of global wheat – which is lower than I’d expect, given Kansas’ reputation.1

** But not for all of us. UNICEF and the WHO estimate that 2.33 billion people faced food insecurity last year, exacerbated by the COVID pandemic and the war in Ukraine.2

*** Even more so, given that plants don’t have the luxury of walking away from funny-smelling water or ominous spores.

† It’s very hard to measure this, though – other global estimates range anywhere from 10% to 40%.

†† The “R”, with the creativity that scientific naming is known for, stands for “resistance.” 9

††† This process, called CODIT (compartmentalization of decay in trees) is why you sometimes see big brown blotches in old tree rings – these are areas that got walled off.12

But even with these strategies, honed for millennia by evolution’s ruthless scalpel, our crops still need help. When you look out across these fields, shading your eyes from the late-summer sun and watching the cornstalks wave, you may notice a chemical tang hanging in the air. This is just a whiff of the more than one billion pounds of insecticides, herbicides, and fungicides that U.S. agriculture consumes every year.13 Throughout the world, the chemical warfare we inflict on our food is merciless and total. The environmental impact alone is enormous: wildlife dies, rain acidifies, and coastal waters from the Gulf of Mexico to the Ganges River are contaminated for decades.14-17 But then, you might remark while watching carpenter bees flit lazily from one leaf to another, if plants have such robust immune systems, why do our crops need all these pesticides? That’s a good question,* one that has received a lot of research attention.18-21 One explanation is that modern farming practices make plants less able to resist disease. Traditionally, agriculture was focused on smaller family farms, which rotated crops out during different growing seasons – wheat one year, clover the next, letting the soil cycle nutrients and recover.22 Today, the landscape is dominated by larger farms, which produce over 80% of U.S. agricultural output.23 Overwhelmingly, the fields at these larger farms are monocropped: they grow only one crop, over and over.24,25 These plants are all genetically similar, and herbicide use lowers biodiversity even further.24 Evidence suggests that pathogens are more abundant in monocropped fields, as soils acidify and beneficial microbes die off.26-28 As a potato farmer in 1800s Ireland could tell you, this is dangerous – disease moves through monocropped fields like wildfire.

*One answer: maybe we don’t need all these pesticides, or at least not in the quantities we use them.

And the problem is getting more urgent. In recent years, as temperatures rise and globalization links different bioregions together, diseases once confined to specific areas have begun spreading worldwide.29 Maize lethal necrosis virus, first observed in Peru, now infects up to 70% of corn seeds in parts of Africa.30 Coffee leaf rust, a fungus endemic to Sri Lanka, has popped up in Brazil and Nicaragua, upending decades of confident predictions that it would never cross the Atlantic.31 Warm-weather insect species, previously held in check by the sterilizing effects of winter, are marching toward the poles as temperatures warm, threatening temperate zones.32 As they spread, these diseases change and shift: much as MRSA and E. coli develop antibiotic resistance in hospital ICUs,33 our constantly-sterilized farmland provides great selective pressure to create agricultural superbugs. One Brazilian study found that a common citrus fungus can develop immunity to fungicide in just two years.34 The coffee leaf rust that jumped the Atlantic? It’s wiped out entire farms, evading local farmers and coffee multinationals’ best efforts.31,35 Only two species of coffee plants*account for nearly all the world’s coffee, and rust kills both.35 Their identical immune systems are ripe for takeover by a disease specialized to attack them. Farmers (and their pesticides) simply can’t keep up.

The clouds are darkening on the western horizon, and a faint promise of rain hangs in the air. You look out at the cornfield, taking in the greenery. Then you notice – it’s not just corn. Interspersed with the ripening stalks are rows of low soybean plants, their pods spilling over the dark soil, and in the distance, you can see a few orderly patches of sedge and ryegrass. This farm is intercropping – growing multiple crops together on the same land. Intercropping is an ancient practice. For centuries in pre-Columbian America, the “Three Sisters,” corn, beans, and squash, were grown in the same fields, each plant strengthening the others.36-38 Today, intercropping is gaining traction among many farmers – it raises productivity, improves nitrogen fixation, and strengthens the soil microbiome, making it harder for pathogens to spread.39-41 One study from the University of Florida found that intercropping even reduces crop loss to insects.41 It’s not entirely clear why, but one hypothesis is that most destructive species are “specialists” in one crop; in multi-cropped fields, less destructive “generalist” insects are at an advantage.42 Intercropping may also provide a level of “biological control,” allowing the natural enemies of pests, like predatory insects, to keep them at bay.43 This process is key to regenerative agriculture, farming practices that mimic natural ecosystems. It works hand-in-hand with a new high-tech solution – plant immunotherapy. Derivatives of CRISPR, the Nobel Prize-winning gene editing technology, can be used to target viral DNA when it enters plant cells, or splice out the genes that viruses and fungi use as footholds to enter.44 Early results are promising – in crops as diverse as cucumbers, rice, and tomatoes, these methods induce resistance to common pathogens.44 Another strategy uses tiny interfering RNA molecules that mediate viral resistance,** engineering them into plant genomes to recognize and attack viruses as they try to replicate.45 Crops can even be modified to produce animal antibodies,46 which our immune systems use to recognize viruses.***

* Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora, or as your friend with a $300 French press will call them in his monologue about acidity and floral undertones, arabica and robusta.

** This process, called RNAi, is fascinating, complicated and still being unraveled in many systems. In humans, small interfering RNA molecules have potential applications in everything from genetic diseases to cancer research. These tiny strings of molecules can be powerful.

*** They’re called “plantibodies.” I take back what I said about scientific naming, that’s gold.

It’s raining now. One of those late-summer storms, heavy drops punctuated by bouts of low thunder, blowing through fast and hard from the west. Already, the crops look refreshed; leaves a little greener, stalks standing thirstily at attention. You get back in the car. The dirt roads turn muddy fast, and it’s best not to get caught out here for long. All around, a sea of green stretches past the horizon, a constant cycle of life and death, threat and promise. This land is a battlefield in the endless fight to feed the world. Time will tell who wins it.

Colter is a first-year Ph.D student in Molecular and Cellular Pathology, studying nuclear protein dynamics and regulation in neurodegenerative disease. In his free time, he enjoys painting and hiking around Ann Arbor, board games with friends, and trying (and mostly failing) to like running.