Written by Kayla Moehn

Edited by Deanna Canizzaro and Amanda Bekkala

Illustrated by Danny Cruz

Growing up, I loved visiting local restaurants with my family, and these shared meals were usually quite eventful.

In New Mexico, the start of most meals is marked by the waitress placing a basket of freshly baked tortilla chips and red serving dishes filled with salsa on the table. It’s understood that the salsa is for adults because it can be very spicy. However, that doesn’t always deter kids from wanting to be like the grown-ups, and I was no different.

As a child, I remember bravely taking a chip and submerging it in salsa before my parents could move it away.

“Oh no! Be careful, KK. That is very hot and for grown-ups only,” my mother warned.

I wanted to be like my parents, though. I may have only been five, but I wanted them to know that I was not a baby. Against my mom’s advice, I shoved the salsa-soaked chip in my mouth. Tears streamed down my face as an intense burning pain filled my mouth. “Ouch! Mommy, this hurts,” I sobbed. I didn’t understand why she and my dad could enjoy something that caused such discomfort in my mouth.

My parents both chuckled while my dad handed me the bottle of honey on the table. Quickly, I squeezed a dollop of honey onto a new tortilla chip and shoved it into my mouth. I kept shoveling honey-coated chips into my mouth until the sweetness of the honey overpowered the unpleasant spiciness of the salsa. Finally, my mouth felt normal again, and a smile found its way to my face as I savored a New Mexican staple for children who are deemed unready for spice.

Eventually, the waitress returned to our table to take our orders. “Red or green?” she inquired. Every New Mexican understands the meaning of this question. She wanted to know if I wanted red or green chile smothered over my meal, a New Mexican tradition.

“She will have neither,” my mother chuckled.

As a child and then adolescent who struggled with eating like a “New Mexican”,I wondered why chile induced such profound pain in my lips and tongue while sparing others. Were others just pretending to like it?

This question continued to simmer in my mind until college, where I majored in genetics at New Mexico State University – home to the Chile Pepper Institute (CPI). The CPI is an international leader in the science of spicy foods. During a class field trip to the CPI’s teaching garden, I first started to uncover some of the answers to my burning questions.

There, surrounded by rows of colorful, sun-soaked peppers, I discovered how scientists carefully breed chiles to craft unique flavors and heat profiles. The diversity of chile was evident in the 150 varieties throughout the garden that varied in size, color, and flavor. Some peppers had small purple fruits packed with high levels of spicy capsaicin – the chemical responsible for inducing the burning sensation that haunted me at family dinners – while others had larger and sweeter fruits with no traces of capsaicin.1 The most commonly grown chile varieties in New Mexico belong to the Capsicum annuum species, which includes New Mexico chile pepper varieties, along with paprika, jalapenos, and cayennes.2 These varieties contribute to the trademark smokey, spicy, and sweet flavor of New Mexican cuisine and differentiate it from the spicy cuisine of other cultures.

My field trip to the CPI teaching garden left me with much to contemplate. Chile peppers were more than just the red and green spicy nuisances of my childhood dinners – they were carefully cultivated and culturally sacred.

Still, knowledge of the wondrous diversity of chile peppers didn’t erase the sting.

One morning in college, I remember sitting outside with my friends at a restaurant under the sunny New Mexican skies. A basket of chips and a variety of green and red salsas sat on the table. To an outsider, this looked like the perfect day, however, I was feeling a little nervous.

My friends quickly started to snack on salsa-covered chips. Before I knew it, everyone was sharing their opinions on the four different salsas that sat on our table. I grew increasingly anxious that everyone was about to discover my sensitivity to spice. In that moment, I was transported back to being the five-year-old who wanted nothing more than to fit in with the others around the table.

“Kayla, you’ve been awfully quiet…which salsa is your favorite?”

My heart was racing. I desperately wanted my friends to think that I could handle the heat. I grabbed a chip and dipped it in the green salsa. “I think I like this one,” I said shakily as I shoved the chip in my mouth. Almost instantaneously, an alarm sounded in my mouth as the tiny capsaicin molecules in the jalapenos dispersed onto my tongue.

Against my better judgment, I grabbed a cold glass of water and tried to feign nonchalance. This only made the pain more intense as capsaicin – which does not dissolve well in water – spread more widely around my mouth.3 Sensory neurons throughout my mouth began to fire nonstop, inducing this uncomfortable sensation.

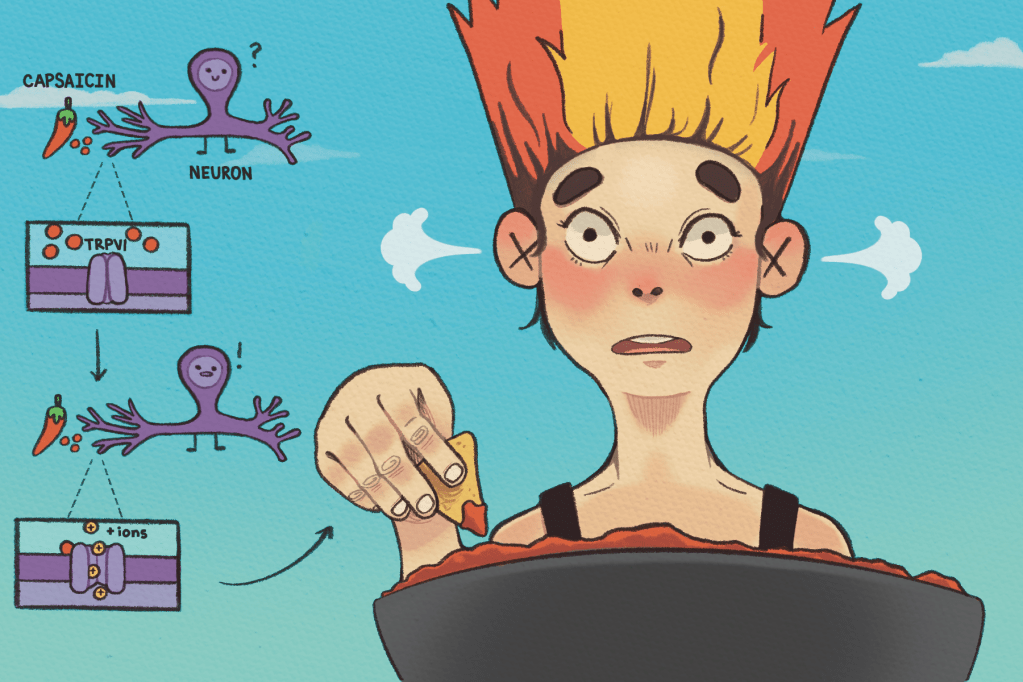

Unlike neurons in the brain, sensory neurons are packed with special detectors that enable them to sense hot/cold, chemical compounds like capsaicin, and touch.4 Surprisingly, the identity of the capsaicin-detecting receptor remained a mystery to scientists for a long time. It was not until 1997 that Dr. David Julius and his research team discovered the molecular blueprint and structure of the detector and later named it TRPV1 (pronounced trip-VEE-wuhn).5,6 Since its discovery, researchers have found that TRPV1 can detect more than just capsaicin, including hot temperatures and acidic pH.7,8

When capsaicin binds to TRPV1, the detector changes shape, similar to a key (capsaicin) unlocking the door (TRPV1) to your home (neuron). Instead of letting people through, TRPV1 opens to allow positively charged ions like calcium and sodium to rush into the neuron. This influx of positive charge causes the neuron to send an electrical signal to the brain that is interpreted as a painful, burning sensation.9

As a college student, I was unaware of the details of this molecular dance, and frankly, all I was concerned with was fitting in with my friends. Throughout the meal, I did my best to hide my pain, as I continued to cautiously eat just enough salsa-coated chips to deter any suspicion that I was an impostor.

Towards the end of my meal, I noticed something strange.

As I continued to eat more salsa, the alarm bells in my mouth lessened. I still felt uncomfortable, but the bite of the salsa stung less. Slowly, I started to notice the earthy and somewhat citrusy flavors of the jalapenos and tomatillos in the salsa. Is this why my family and friends enjoyed eating spicy foods?

It was not magic that made the burning sensation slowly fade. This phenomenon – called neuronal desensitization – occurs when sensory neurons that express TRPV1 become less responsive to capsaicin after repeated exposure.10 This is similar to when you enter a cold pool. At first, you might feel a lot of discomfort, but eventually your body becomes accustomed to the temperature and your cold-sensing neurons stop firing.

It remains an open question about how desensitization to capsaicin occurs, but scientists have some ideas.6,9 One hunch is that continued capsaicin detection and neuronal firing are taxing on the neuron and deplete its resources. As a consequence, the neuron may either become less responsive to replenish its supplies or die.

As I left the meal with my friends, I felt newly empowered to take on the spicy world of New Mexican food. With each spicy encounter, the sensory neurons in my mouth that detect capsaicin began to change. They gradually became less sensitive to the heat, allowing the complex and rich flavors of New Mexican food to shine through more clearly. Increasingly open to trying spicy foods, I left college not only with a tolerance for spice but also a larger appreciation for my culture’s cuisine.

Motivated to learn more about sensory neuroscience, I moved to Michigan to pursue my PhD and serendipitously joined the lab of Dr. Joshua Emrick, who trained under the mentorship of Dr. Julius, the scientist who uncovered the identity of TRPV1 (and later won a Nobel Prize for the discovery). My passion for understanding sensory receptors and neuroscience as a whole has allowed me to explore a new perspective of New Mexican cuisine, even far from home.

Here, I often find myself with new friends from the Midwest who have yet to be accustomed to spice. As we enjoy a meal together, they eye a bowl of salsa with suspicion. I dip a chip generously, smile, and say, “This isn’t spicy at all!” A glimmer of courage flashes in their eyes as they take a chip and give it a try. They try to hide their wince.

“It gets better. I promise.”

Kayla is a neuroscience PhD student on a quest to understand how the nervous system lets us sense the world. In the lab, she develops novel ways to study tooth and other orofacial pain in rodents. Outside of science, she enjoys golfing, watching Breaking Bad, and spending time with her boyfriend and two adorable cats, Dewey and Peanut Shell.