Written by Hyunwoo Jang

Edited by Jeremy Chen and Alex Ford

Illustrated by Naomi Raicu

Introduction

Imagine yourself in the driver’s seat, approaching an intersection. The traffic light ahead shifts from green to yellow, then quickly to red. Almost without thinking, your foot moves to the brake, and your car rolls to a stop. It’s a routine gesture – an automatic response when you perceive a red light. But consider: what exactly are you experiencing when you see that red light? We all learn to stop at red, yet can we be sure that the “redness” you perceive is the same as someone else’s? On the surface, everyone seems to agree on what “red” means, but perhaps your experience of red differs from mine, even if we both call it by the same name.

This seemingly trivial question opens a fascinating doorway into one of science’s deepest mysteries: consciousness. Each of us lives within our own first-person perspective. We are aware of our surroundings, feelings, and thoughts. We often take this for granted – a notion captured by Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am.” Yet consciousness remains remarkably elusive and poorly understood by today’s science.1 Despite the ability to measure and describe the brain’s physical processes, the subjective quality of experience – what it feels like to see red – remains fundamentally mysterious.2 How do neurons firing electrical signals translate into the rich tapestry of perception that fills our waking moments?

Known facts of color perception

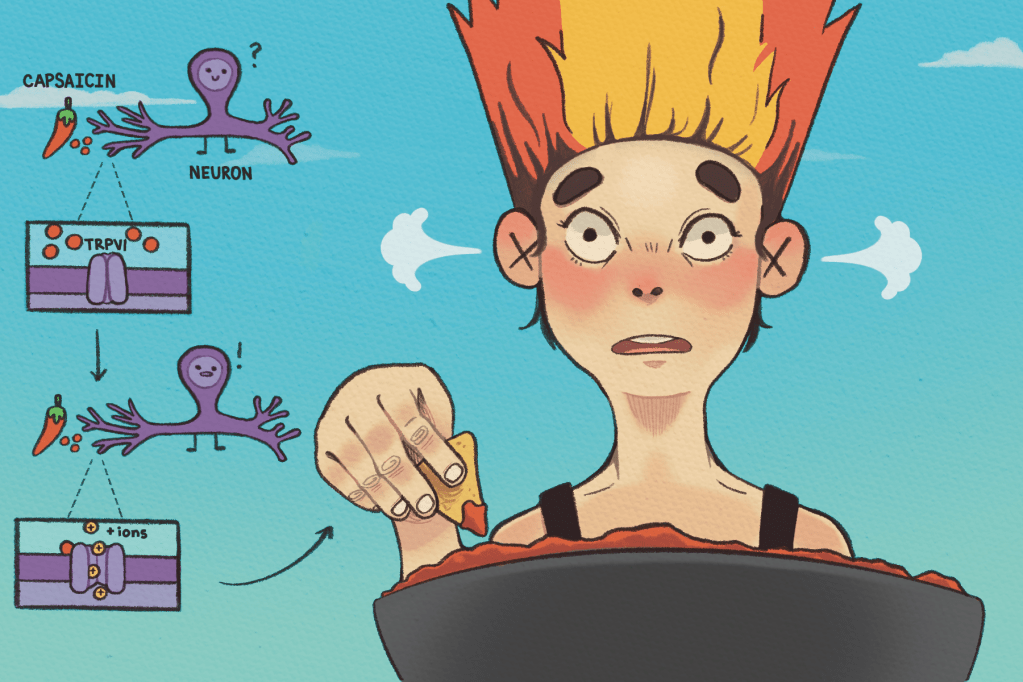

To explore the mystery of subjective color experience, it’s helpful to first understand how color perception works from a scientific perspective. Color begins with light – specifically, electromagnetic waves of different wavelengths.3 The visible spectrum spans roughly 400 to 740 nanometers (nm): waves near the lower end (~400nm) are perceived as violet to blue, while those toward the upper end (~740nm) appear orange to red. When light waves reflect off an object and enter your eye, they strike the retina at the back, where specialized photoreceptor cells called cones are activated.4 Humans typically have three types of cones, each most sensitive to a different part of the light spectrum: one for blue, one for green, and one for red – and like a painter mixing primary colors to create their palette – all the colors you will ever see arise from different combinations of these three cones activating That’s why color blindness occurs when one or more types of these cones are missing or malfunctioning – leading to difficulties in distinguishing certain colors – most commonly red and green.5

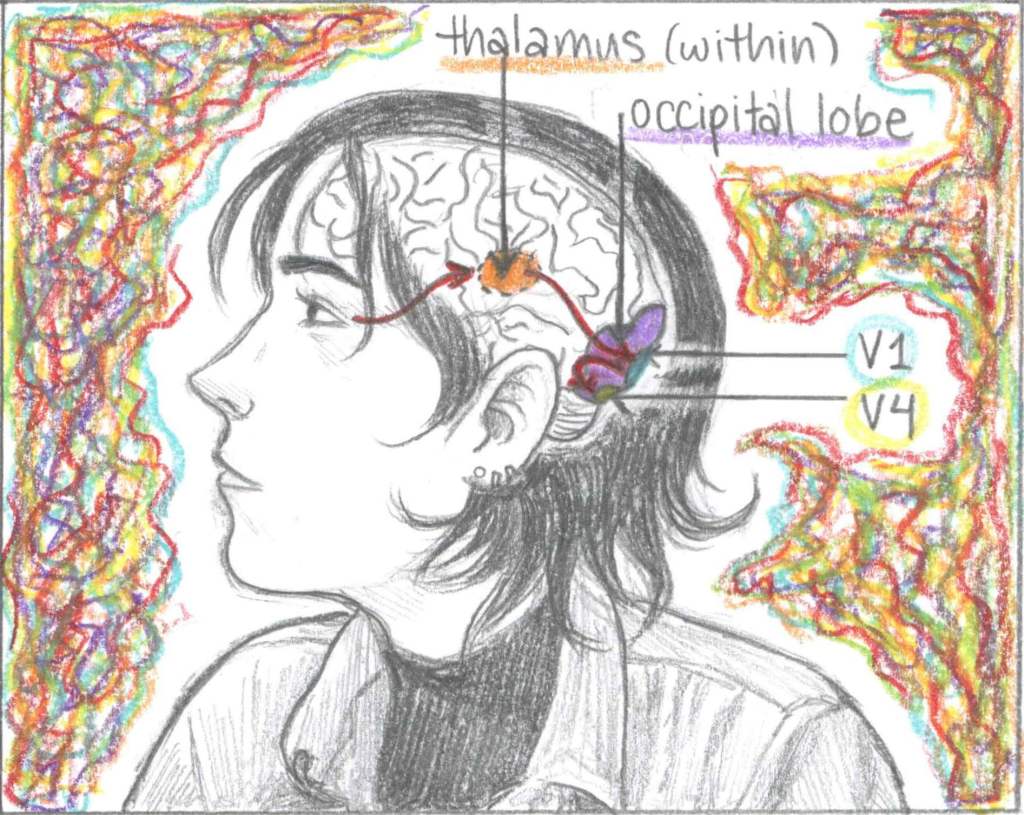

Once these cones detect light of their preferred wavelength, they convert it into electrical signals that travel back along the optic nerve.6 These signals are routed through the thalamus to the primary visual cortex (V1) at the back of your brain,7 before then passing onto regions like the 4th visual area (V4), which play a critical role in shaping our perception of color8 Other brain regions integrate color signals with context, memory, attention, and even emotion, enriching the raw sensory input into the vivid experiences we recognize as a “color”.9–11

The Inverted Spectrum

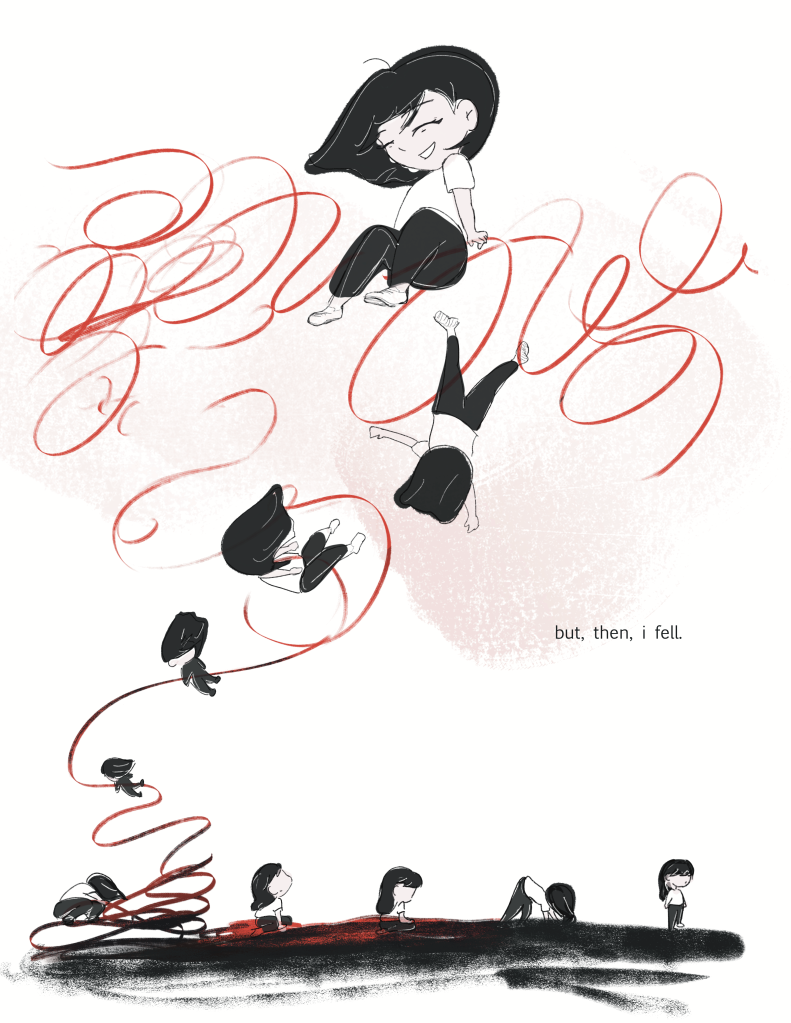

However, today’s science has no direct way to access the subjective contents of another person’s mind. This is what philosopher Joseph Levine called the “explanatory gap”: the disconnect between our understanding of the brain’s structure and physical processes, and the internal experiences that arise from it12,13. In theory, we cannot logically rule out the possibility that two people experience light with the same wavelength differently. To illustrate this, philosopher John Locke first proposed the inverted spectrum thought experiment in the 17th century14. In essence, your experience of “red” might correspond in your friend’s mind to what you would call “green”.15 Yet, you both learn to label that wavelength “red” by associating it with stoplights, apples, or roses, never by comparing internal experiences directly. As a result, any such inversion would go completely undetected.

What makes the inverted spectrum especially intriguing is that, unlike color blindness – which results from physical deficiency in cone cells – this thought experiment asks whether two people with fully functional visual systems might still have different subjective experiences. It’s like wondering if we’re all walking around with a secret, personalized color filter in our heads – a thought that might make you look at the next person wearing a “hideous” color combination with a bit more sympathy.

Definition of qualia

This hidden, first-person quality of perception is captured by the concept of qualia.2 Qualia are the subjective “what-it-is-like” of seeing red, feeling pain, or tasting sweetness. They are the internal units of conscious experience. While some may argue that qualia are illusory16–18, or just byproducts of neural processes limited by our current understanding of the brain19 – it is apparent that they are more than simply informational outputs of neural circuits; they are the lived sensations that only the experiencing subject can access.

Since the 1990s, the concept of subjective experience as a vital feature of consciousness has gained momentum20. Although precise definitions remain elusive, qualia pose a core challenge for any comprehensive theory of mind. This trend has driven researchers to confront the so-called “hard problem” of linking first-person experiences with third-person measurements of brain activity, bringing the debate about qualia from the philosophical margins to the forefront of scientific inquiry21–23.

Qualia space

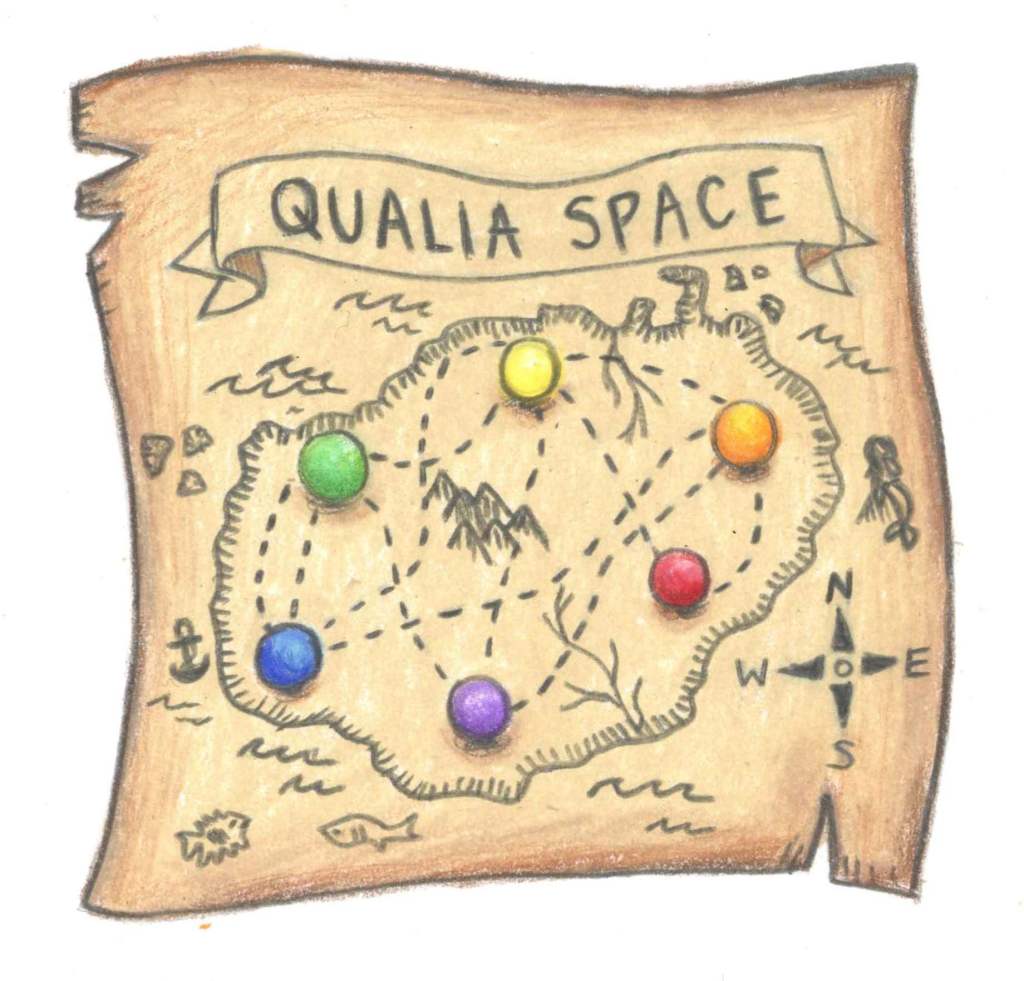

Recently, a research team led by Dr. Naotsugu Tsuchiya explored a concept called “qualia space24.” It is a framework that treats qualia as if they were points in a kind of mental map, where the spatial distances between them reflect how similar or different they feel25. For example, is your experience of “orange” somehow “located” between your experiences of “red” and “yellow”? By asking participants to rank the similarity between color combinations, a personalized map of color experiences forms.

In a recent study, Tsuchiya’s team collected color similarity judgments from children of various ages and cultures26. Their findings revealed a striking consistency in the structure of color qualia space across all groups. This suggests that while your personal experience of “red” might differ from someone else’s, the relationships between colors – the way orange feels between red and yellow – are remarkably stable across humans. In other words, even if my “red” is your “green,” my “orange” would likely be your “blue-green”: the relational pattern stays intact.

Excitingly, this method isn’t limited to color: similar approaches are being used to map qualia spaces for sounds, smells, and even complex emotional or bodily experiences27,28. Ultimately, researchers hope these local qualia spaces can be integrated to better understand how diverse sensory experiences merge into a unified conscious experience29. The qualia space concept can also be applied to brain imaging. By visualizing brain activity with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, and combining that with similarity rankings, scientists can construct a “neural qualia space,” mapping brain patterns that correspond to specific qualia30. This allows researchers to directly relate subjective experiences to measurable neural activity – progress toward uncovering the elusive “neural correlates of consciousness”31. Thus, the combination of qualia space with neuroimaging may allow us to “translate” between the language of neurons and the language of experience.

Additional questions about consciousness and qualia

Inquiry into consciousness and qualia has practical relevance in today’s world of advanced artificial intelligence. Most experts believe that current AI systems like ChatGPT do not truly experience qualia, since they merely manipulate symbols and patterns to mimic human-like reasoning32. However, at the core of ChatGPT’s architecture, language is represented in an abstract space where relationships between words are mapped – this is what the system learns during training33,34. For example, it learns that the relationship between “king” and “queen” is similar to that between “prince” and “princess,” forming something akin to a language qualia space. Now, emerging multi-modal AI systems integrate sensory inputs such as vision, speech, and tactile feedback, mirroring the multidimensional nature of human perception35–37. If such an AI system builds its own structured representation – similar to a qualia space – across multiple modalities, could we confidently say it remains non-conscious? These questions push the boundaries of our understanding of consciousness, ethics, and what it might mean in the future to coexist with entities that may one day claim sentience.

Conclusion

The concept of qualia reminds us that consciousness remains one of the final frontiers of human knowledge. While we’ve made remarkable progress in understanding the brain’s physical processes, the subjective nature of experience – why there is “something it is like” to see red or feel pain – continues to elude scientific explanation38. Interestingly, most of us (even neuroscientists!) rarely reflect on this profound mystery, even though it is the foundation of every waking moment39. So the next time you’re waiting at a red light, take a moment to marvel not just at the color, but at the astonishing fact that you can experience it at all: the dance of sunlight through leaves, the layered scent of a forest, the emotional pull of music. Each represents a miracle of consciousness that science is only beginning to understand.

Hyunwoo Jang is a Ph.D. candidate in the Neuroscience Graduate Program at the University of Michigan and a researcher with the university’s Center for Consciousness Science. He is also the founder and current president of the Korea Association for Consciousness Sciences. His work focuses on how large-scale brain networks reorganize across different states of consciousness. Beyond the lab, he is an active freelance translator and author.

References

- The Science of Consciousness. (Routledge, London, 2003). doi:10.4324/9780203360019.

- Kanai, R. & Tsuchiya, N. Qualia. Current Biology 22, R392–R396 (2012).

- Waldman, G. Introduction to Light: The Physics of Light, Vision, and Color. (Courier Corporation, 2002).

- Nathans, J. The Evolution and Physiology of Human Color Vision: Insights from Molecular Genetic Studies of Visual Pigments. Neuron 24, 299–312 (1999).

- Hunt, D. M. & Carvalho, L. S. The Genetics of Color Vision and Congenital Color Deficiencies. in Human Color Vision (eds. Kremers, J., Baraas, R. C. & Marshall, N. J.) 1–32 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2016). doi:10.1007/978-3-319-44978-4_1.

- Meister, M. & Berry, M. J. The Neural Code of the Retina. Neuron 22, 435–450 (1999).

- Kandel, E. R., Schwartz, J. H. & Jessell, T. Principles of Neural Science, Fourth Edition. (McGraw-Hill Companies,Incorporated, 2000).

- Heywood, C. A., Gadotti, A. & Cowey, A. Cortical area V4 and its role in the perception of color. Journal of Neuroscience 12, 4056–4065 (1992).

- Zeki, S. & Marini, L. Three cortical stages of colour processing in the human brain. Brain: a journal of neurology 121, 1669–1685 (1998).

- Tootell, R. B., Nelissen, K., Vanduffel, W. & Orban, G. A. Search for color ‘center (s)’in macaque visual cortex. Cerebral Cortex 14, 353–363 (2004).

- Parra, M. A., Della Sala, S., Logie, R. H. & Morcom, A. M. Neural correlates of shape–color binding in visual working memory. Neuropsychologia 52, 27–36 (2014).

- Levine, J. Materialism and qualia: The explanatory gap. Pacific philosophical quarterly 64, 354–361 (1983).

- Humphrey, N. Seeing Red: A Study in Consciousness. (Harvard University Press, 2006). doi:10.4159/9780674038905.

- Locke, J. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. (Samuel Marks, 1825).

- Shoemaker, S. The inverted spectrum. The Journal of Philosophy 79, 357–381 (1982).

- Dennett, D. C. Consciousness Explained. (Hachette+ORM, 2018).

- Sarıhan, I. Deflating the hard problem of consciousness by multiplying explanatory gaps. Ratio 37, 1–13 (2024).

- Frankish, K. Illusionism: As a Theory of Consciousness. (Andrews UK Limited, 2017).

- Churchland, P. M. Reduction, qualia, and the direct introspection of brain states. The journal of philosophy 82, 8–28 (1985).

- Seth, A. K. Consciousness: The last 50 years (and the next). Brain and Neuroscience Advances 2, 2398212818816019 (2018).

- Chalmers, D. The Hard Problem of Consciousness. in The Blackwell Companion to Consciousness (eds. Schneider, S. & Velmans, M.) 32–42 (Wiley, 2017). doi:10.1002/9781119132363.ch3.

- Seth, A. K. & Bayne, T. Theories of consciousness. Nat Rev Neurosci 23, 439–452 (2022).

- Dennett, D. C. Sweet Dreams: Philosophical Obstacles to a Science of Consciousness. (MIT Press, 2005).

- Tsuchiya, N., Phillips, S. & Saigo, H. Enriched category as a model of qualia structure based on similarity judgements. Consciousness and Cognition 101, 103319 (2022).

- Kawakita, G., Zeleznikow-Johnston, A., Takeda, K., Tsuchiya, N. & Oizumi, M. Is my “red” your “red”?: Evaluating structural correspondences between color similarity judgments using unsupervised alignment. iScience 28, (2025).

- Moriguchi, Y. et al. Comparing color qualia structures through a similarity task in young children versus adults. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 122, e2415346122 (2025).

- Welch, D. et al. Assessment of qualia and affect in urban and natural soundscapes. Applied Acoustics 180, 108142 (2021).

- Castro, J. B., Ramanathan, A. & Chennubhotla, C. S. Categorical dimensions of human odor descriptor space revealed by non-negative matrix factorization. PloS one 8, e73289 (2013).

- Edelman, G. M. & Tononi, G. A Universe Of Consciousness: How Matter Becomes Imagination. (Basic Books, 2008).

- Hirao, T. et al. A neuroimaging dataset during sequential color qualia similarity judgments with and without reports. Scientific Data 12, 389 (2025).

- Koch, C., Massimini, M., Boly, M. & Tononi, G. Neural correlates of consciousness: progress and problems. Nat Rev Neurosci 17, 307–321 (2016).

- Gouveia, S. S. & Morujão, C. Phenomenology and artificial intelligence: introductory notes. Phenom Cogn Sci 23, 1009–1015 (2024).

- Sharma, P., Jyotiyana, M. & Kumar, A. V. Applications, Challenges, and the Future of ChatGPT. (IGI Global, 2024).

- Wu, T. et al. A brief overview of ChatGPT: The history, status quo and potential future development. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 10, 1122–1136 (2023).

- Liang, P. P. Brainish: Formalizing A Multimodal Language for Intelligence and Consciousness. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2205.00001 (2022).

- Mogi, K. Artificial intelligence, human cognition, and conscious supremacy. Frontiers in psychology 15, 1364714 (2024).

- Solms, M. The Hidden Spring: A Journey to the Source of Consciousness. (W. W. Norton & Company, 2021).

- Nagel. What Is It Like to Be a Bat? The Philosophical Review (1974).

- Wallace. The Taboo of Subjectivity: Toward a New Science of Consciousness. Oxford University Press (2004).