Author: Ryan Farber

Editors: Alex Taylor, Jessica Cote, and Sarah Kearns

Where do you come from? Somewhere on Earth, you say. But how did life begin? How did the Earth begin? How did the Sun begin? … How did the universe begin? These questions of origins have fascinated humanity for millennia. And though we can answer neither the first question nor the last, nor many in between, modern astronomical theory places a handle on the origins of one structure of particular importance for our existence: the Sun.

In this origin story, we will begin in the dark, sparse, altogether quite inhospitable, domain of interstellar space. In fact, if we consider a cubic centimeter of space, we would find only one lonely hydrogen atom, the hero of our story.

Our hero is not a hydrogen atom by lucky chance either. About 92% of all the matter in the universe is hydrogen1. Another 7% of the universe is made up of helium, leaving less than 1% for all the heavier elements. These heavier elements are generated in stars, bestowing upon them the lovely name of stardust. Life on Earth relies on them: from the oxygen atmosphere we breathe, to the silicon-based computers we use to read this delightful article, our daily lives depend on a teeny-tiny fraction of the stuff comprising the universe. Moreover, stardust will play a profound role in the origin story we are unraveling.

But for now, let us recall our lonely hydrogen atom, sitting in its spacious cubic centimeter of space. Now, one may be thinking, “Big deal! A cubic centimeter is tiny so of course there’s only one atom there. It’s about the same size as a sugar cube-” Exactly! A sugar cube of one cubic centimeter contains a whopping 1021 molecules. That’s a billion trillion molecules. There are only a thousand times more stars in the universe than molecules of sugar in that one cubic centimeter which is home to only one hydrogen atom. That’s just how sparse space is.

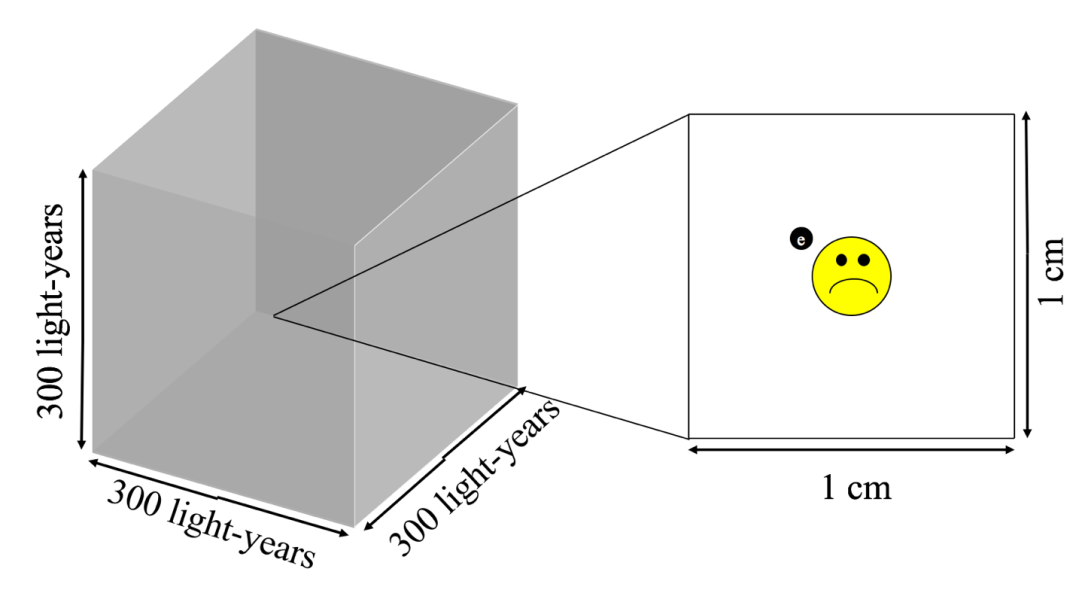

On the other hand, space is vast. Consider a cubical region of interstellar space, with each side spanning 300 light-years2. With one hydrogen atom per cubic centimeter, we expect there to be a mind-boggling 1061 hydrogen atoms in our imaginary cube of space (see Figure 1). That’s about as many atoms of sand as there would be in the entire universe if every star in the universe hosted an Earth-like planet (…and we’re still searching for the second Earth-like planet in the universe).

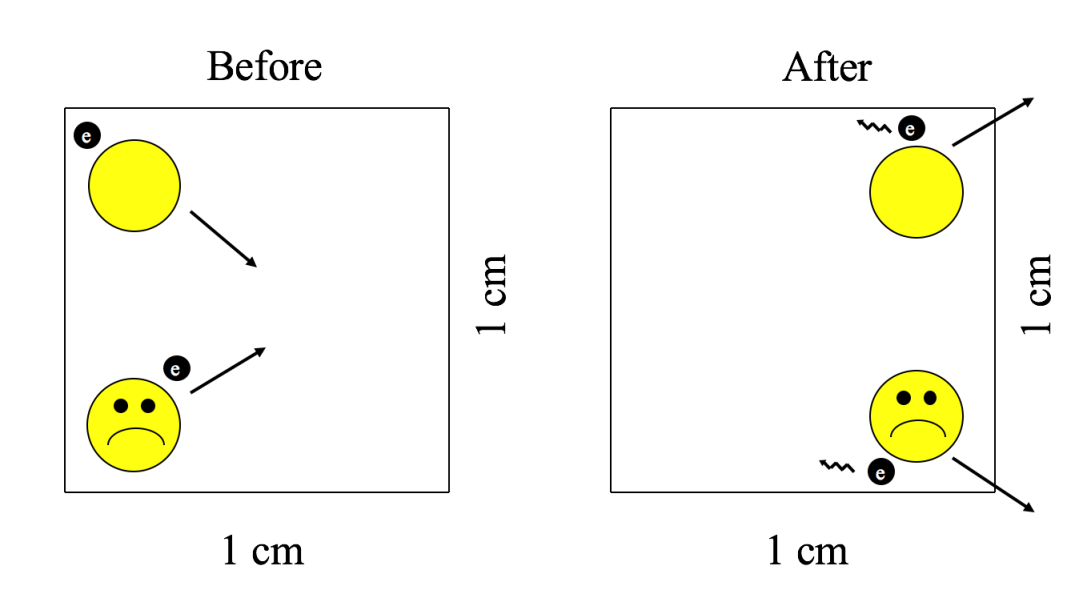

As our lonely hydrogen atom whizzes about space amongst its 10 trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion neighbors, each with its own random trajectory, it is perhaps unsurprising that our hero will occasionally encounter another hydrogen atom. If they happen to approach close enough, their constituent protons will repulse one another, and the two atoms will whizz back apart. No harm, no foul? Not quite. Similar to how billiard balls lose energy during a collision (as evidenced by the sound of the collision), the two hydrogen atoms lose energy during the encounter (emitting light rather than sound; see Figure 2). In typical interstellar space conditions, such a process of encounter and loss of energy proceeds for about 200,000 years, an astrophysical blink of the eye.

As the hydrogen atoms lose energy, the gas they comprise also drops in temperature. The cooling gas contracts, increasing its density. In a higher density environment, it is more likely that atoms will collide, accelerating the cooling process. When the density has increased about one thousand times and the temperature has simultaneously reached a frigid 5 K (-450 °F; for comparison, the coldest Antarctica has ever been was a balmy -128 °F), the stardust enters the picture.

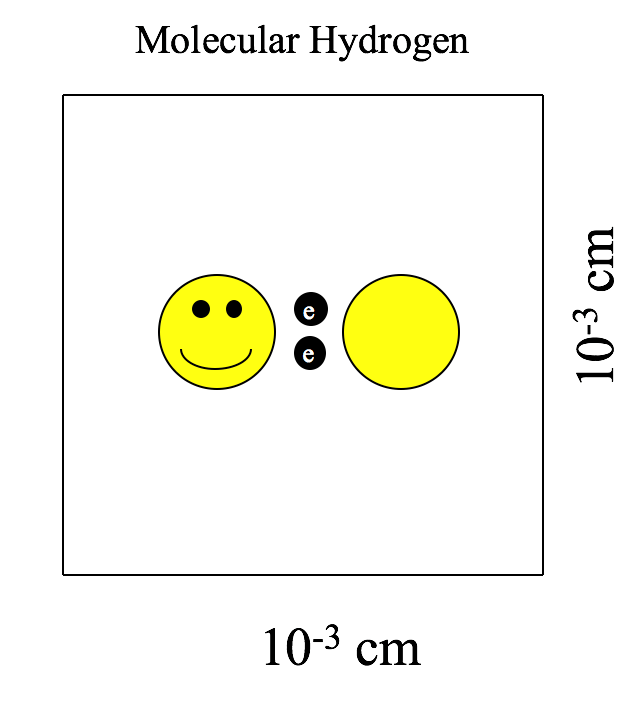

Molecular hydrogen (H2) cannot form simply by sticking two hydrogen atoms together in free space like Velcro and hoping that they stay joined together. As mentioned previously, the protons will repulse one another. Instead, the hydrogen atoms first bind to particles of stardust. The close quarters enforced by the dust enables the hydrogen atoms to overcome their mutual repulsion and enter a bound state. The formation of molecular hydrogen releases some energy, unbinding the molecular hydrogen from the dust (see Figure 3). When the majority of our 1061 hydrogen atoms have formed molecular hydrogen, they form a new structure called a giant molecular cloud (see Figure 4).

At such a low temperature, there is essentially no pressure to halt the gravitational collapse. Piece by piece, the giant molecular cloud fragments into separately collapsing cloudlets, each attaining yet higher densities. Hurtling faster than a rocker re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere, millions upon millions of molecules of hydrogen are all squished into the once cozy cubic centimeter of space. When collisions occur at such breakneck speeds, the interaction is nothing like the tranquil cooling process of Figure 2. Instead, the temperature furiously increases, disintegrating the molecular hydrogen back into atoms. The hydrogen atoms are rapidly ionized (stripped of their electrons). The free-floating electrons speed through the cloud, disintegrating more molecular hydrogen back into atomic form. The cloudlet’s collapse is halted when the temperature has increased sufficiently that the resulting pressure counteracts the inexorable force of gravity. The temperature now vastly exceeds the typical interstellar value. As the very core of the cloud is crushed by the billion trillion trillions of hydrogen nuclei above, the temperature attains a scorching ten million Kelvin. The hydrogen nuclei are packed so densely and are racing so quickly that a fortunate pair collide and fuse, transforming a hydrogen nucleus into a helium nucleus (see Figure 5). Fusion releases a prodigious amount of energy, marking the birth of a new star.

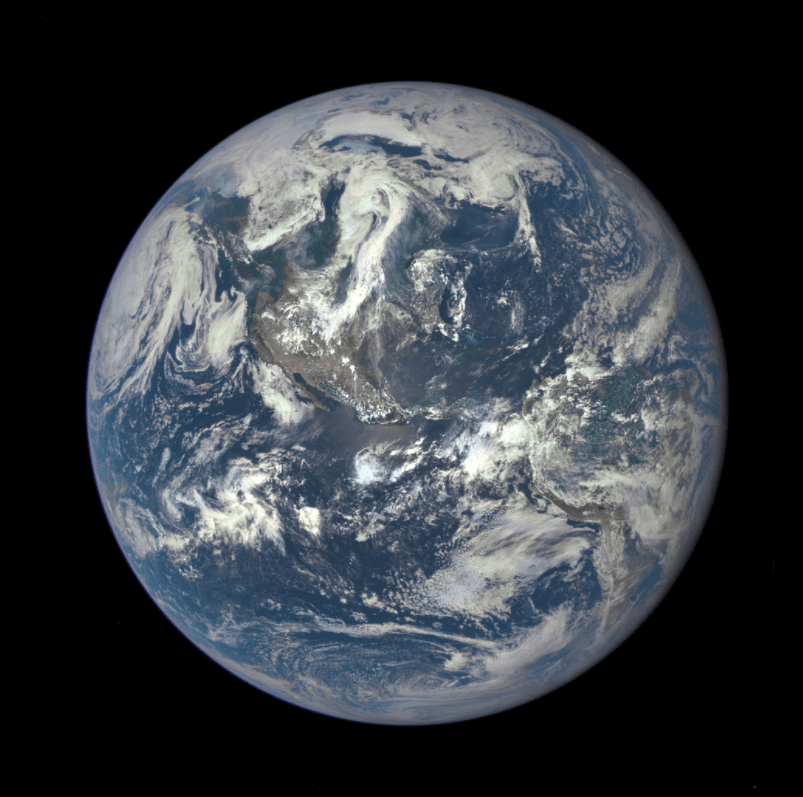

The stellar nursery of a giant molecular cloud host hundreds of newly formed stars. And once upon a time, from its own stellar nursery, a dull yellow star began fusing hydrogen. 93 million miles from the star, a coalescence of astronomically minuscule traces of stardust, all but forgotten by the universe, gave birth to our Earth (see Figure 6). So weigh heavy in your hearts that space is not empty, for without the scores of light-years of lonely hydrogen atoms, dragging with them strands of stardust, we would not be here to ponder the magnificence of space.

1 Note that I am citing the number abundances of the elements, whereas the oft-quoted ~¾ hydrogen, ¼ helium, and 2% heavier elements utilize the mass abundances.

2 A light-year is the distance light travels in one year. Light travels at blazingly fast speeds that put Comcast to shame; for example, light takes only 8 minutes to travel the 93 million miles from the Sun to the Earth. 300 light-years is the size of a giant molecular cloud, which will be described subsequently.

About the author:

Ryan Farber is a third-year PhD student at the University of Michigan, studying Astronomy & Astrophysics. Ryan researches the efficiency with which high energy charged particles (unfortunately named cosmic “rays”) can accelerate galactic outflows. Beyond research, Ryan enjoys cheering on his home and local sports teams, weightlifting, running, and learning languages.

Ryan Farber is a third-year PhD student at the University of Michigan, studying Astronomy & Astrophysics. Ryan researches the efficiency with which high energy charged particles (unfortunately named cosmic “rays”) can accelerate galactic outflows. Beyond research, Ryan enjoys cheering on his home and local sports teams, weightlifting, running, and learning languages.

Read all posts by Ryan here.

Nicely written. Two thoughts came to mind. 1. In your second paragraph you mentioned the ratio of elements with Hydrogen being the most abundant. However Dark Energy and Dark Matter make up far more then hydrogen and all the other elements combined. (But that fact is not what you are concerned with, so it might be a foot note; but maybe an important one as the dark matter can gravitational interact the the forming gas cloud which produces the new star.) 2. Nearby exploding stars can cause shock waves into the gas cloud thus triggering compression of the H molecules to force them into critical mass to start the fusion process.

LikeLike

Dark matter and dark energy have not been proved beyond reproach.

LikeLike

If everything was hydrogen until stars produced heavier elements, and stars need dust to begin the process of accretion, then where did the first stardust come from?

LikeLike

Good catch; I noticed that as well. Until the first star is born everything is hydrogen. And even after the first supernovae the vast majority of everything is still hydrogen. As the author points out even now after some 13.? billion years 92% of everything is still hydrogen. My conclusion is that it didn’t encounter stardust… it more than likely encountered another hydrogen atom.

LikeLike

hmm

LikeLike

How many electrons are in a cubic centimeter of space? Thanks

LikeLike