Author: Katie Wozniak

Editors: Jessica Cote, Noah Steinfeld, and Shweta Ramdas

Five months after the 2016 U.S. Presidential election, many remain confused about how Donald Trump made it into the White House despite leading a seemingly disorganized and unconventional campaign against a more experienced candidate. To understand how this happened, experts have taken a closer look at the campaign strategies employed by Trump, and one major theory is that Trump won the presidency thanks to big data analysis by an analytics company called Cambridge Analytica.

But is there really enough evidence to support that big data won Trump the election?

What Is Big Data?

In the context of the most recent election, big data is all data from our daily habits, both online and offline, that is stored like a digital thumbprint and can then be used by companies like Cambridge Analytica. Every time you swipe your credit card or use a GPS to find your way around, this thumbprint is refined. Cambridge Analytica gathers data on people from sources as diverse as their social media presence, spending information (e.g. which loyalty rewards programs you’re in and what charitable donations you make), TV watching, mobile check-ins, and religious information.

According to the Advanced Performance Institute, a UK-based consulting firm, big data helps companies understand and target customers, including the voting American public. Before the 2016 election, Gurbaksh Chahal, founder of the marketing firm RadiumOne, predicted that employing both social data and big data would help a candidate win the election based on 2008 and 2012 election spending and tactics.

Perhaps the most concrete evidence for the effectiveness of big data comes from a survey of company executives by Forbes Insights and Rocket Fuel, a marketing consultant company that uses big data and artificial intelligence. 92% of companies that used big data said they met or exceeded their goals, and 70% said they could effectively pinpoint their audience in all or most social media efforts.

How Could Big Data Help a Candidate Win an Election?

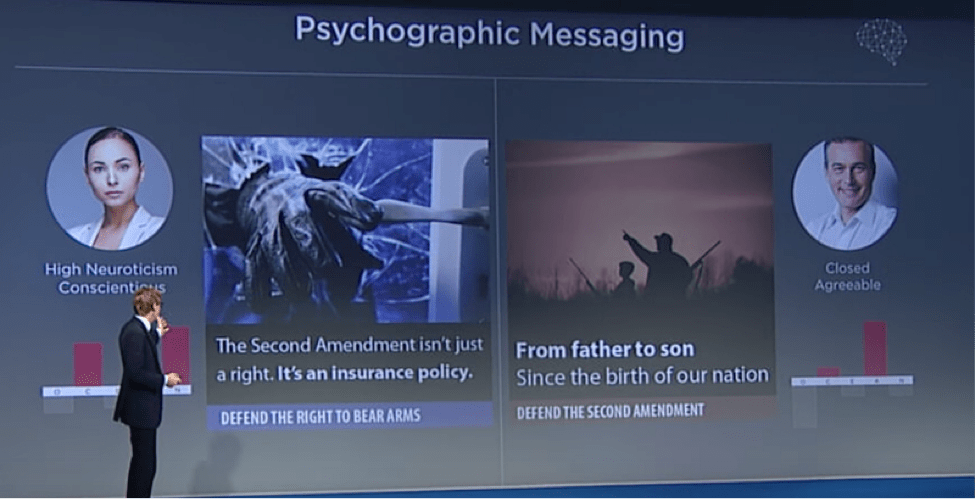

Classically, political campaigns have relied on demographics, but the Trump campaign was using personality profiles created by Cambridge Analytica. The company classifies people into “personality types” based on five criteria: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness and Neuroticism (OCEAN). Ads on social media and TV can then directly target a voter who might easily be swayed politically, an approach that is known as “behavioral microtargeting.”

For the 2016 election, Trump’s campaign used big data to identify voters to determine which specific campaign advertisement will be used. For example, different images were used to captivate different audiences to promote the Second Amendment. An image of an intruder smashing a window would be “for a highly neurotic and conscientious audience the threat of a burglary—and the insurance policy of a gun” and a pleasant view of a field at sunset with a man shooting ducks could be “for a closed and agreeable audience—“people who care about tradition, and habits, and family,” according to Nix.

The Trump campaign also aimed to suppress voting by likely Hillary Clinton voters, including “wavering left-wingers, African Americans, and young women,” whose votes Hillary Clinton needed to win. Facebook ads depicting Clinton speaking unfavorably about a certain voting demographic could be targeted to that same demographic to deter those people from voting. For example, the Trump campaign zeroed in on urban radio stations (which cater to a large black demographic) for their messages about Clinton’s use of the word “superpredators” to describe gang members. Some ads ran: “Hillary Clinton should be ashamed, using racially charged words describing black children as superpredators. Mr. Trump will rebuild the community using our labor, our spirit, and our soul.”

In addition, big data was used to determine where political rallies should be held since it is not possible for all candidates to visit every part of the country. Cambridge Analytica divided the country into 32 personality types and selected 17 states that contain voters with OCEAN profiles suggesting they would vote for Trump. Writers at Motherboard think Trump’s decision to focus more on Michigan and Wisconsin, two large swing states, was a direct result of big data analysis.

Cambridge Analytica even designed a phone app that flagged certain households that were predicted to be highly receptive to Trump’s messages; canvassers would then spend their efforts knocking on those doors with guidelines on how to interact with the personality type of the resident.

What Do Experts Think?

Experts are taking both sides in the debate over whether big data swayed this year’s election. Cambridge Analytica’s CEO clearly thinks his company’s services helped Trump win the election: “The more you know about someone, the better you can engage with them and the more relevant you can make the communications that you send to them, so our job is to use data to understand audiences.”

But he jury is out on whether or not big data truly helped Trump win this election. Michal Kosinski, a Stanford professor who helped come up with the OCEAN criteria, is less certain because there might have been other factors outside of the OCEAN profiles that contributed to this election or the profiles were inaccurate.

Martin Robbins, a writer from Little Atoms magazine, questions the very legitimacy of OCEAN profiling: “OCEAN personality traits would normally be assessed through a questionnaire. To establish them from someone’s Facebook feed is at best an untested piece of science. Is their feed representative? Is it even public or available to you? Is your algorithm 100 percent confident or (more likely) only 75 percent?”

Author and scholar Sue Halpern underscored the fact that collection and implementation of big data are often not without bias—presumption of variables for algorithms are introduced by the creators, which can skew the analysis of what a person is interested in. For example, based on Halpern’s Facebook “likes,” she was most likely a single gay male.

The days of newspaper and radio as primary sources for information are long gone, and political campaign tactics are changing as big data became readily available. But sometimes more data does not necessarily mean clearer trends. Although using big data can be useful in some scenarios like marketing, it is difficult to state that using big data was the main cause for this election’s result.

About the author

Katie is a first-year pre-candidate graduate student in Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology (MCDB) at the University of Michigan. She is in her last of four rotations in the department and will be selecting a lab soon! Before graduate school, she earned her B.S. in Microbiology from Michigan State University. It was at MSU that Katie became excited about scientific research and subsequently studied the evolution of the symbiosis between Medicago polymorpha and Ensifer medicae (a leguminous plant and N-fixing bacteria). In her free time, she enjoys cooking, sour beers, reading, and exercising. Follow Katie on Twitter or find her on LinkedIn.

Katie is a first-year pre-candidate graduate student in Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology (MCDB) at the University of Michigan. She is in her last of four rotations in the department and will be selecting a lab soon! Before graduate school, she earned her B.S. in Microbiology from Michigan State University. It was at MSU that Katie became excited about scientific research and subsequently studied the evolution of the symbiosis between Medicago polymorpha and Ensifer medicae (a leguminous plant and N-fixing bacteria). In her free time, she enjoys cooking, sour beers, reading, and exercising. Follow Katie on Twitter or find her on LinkedIn.

Read more by Katie here.

Image credit

Figure 1: Screenshot from https://youtu.be/n8Dd5aVXLCc?t=3m52s